This game is challenging, and like most things, you can make the learning process a lot easier by leaning on the experiences of veterans in the area you wish to specialise in.

Any success I've had is primarily due to my mentor, Brad, and the investing philosophies he taught me, which align with how I viewed the world and my behavioural makeup.

This didn't prevent me from making more than my fair share of fuck-ups, including a painful one in 2015, which I'll get to…

It did give me a solid foundation to build on with investing.

"Experience is what you get when you don't get what you want"

-Howard Marks

I've always loved Kevin Muir's tag line; “all I bring to the party is twenty five years of mistakes”.

I try to hunt out veterans in the areas I'm interested in and do my best to internalise the rules they've learned from decades in the trenches.

Granted, there are some things I had to learn the hard way.

Most of my rules I stick to religiously, have a painful memory attached from when I ignored the rule.

I've been busy deep-diving into sectors that I haven't touched on these rules since my Crux days (unfortunately, they deleted the entire YouTube collection, so even the links I provided no longer exist).

In this piece, I want to touch on a few things that I weight heavily in markets, along with some rules of thumb attached to them.

Minimum effective dose information?

I recently included Understanding by Adam Robinson in Ferg's Finds, which is primarily an overview of Paul Slovic's study. For those who haven't come across it, here is a quick summary:

“Having more information doesn’t necessarily improve decision-making. We know from studies of horse racing that when handicappers receive more information about horses and riders, they become proportionately more confident even though they are no more likely to pick the winner. When analysts have too much data, there’s a danger they won’t see the wood for the trees.”

What information do I value beyond which I'm likely to increase my confidence without performance improvements?

I'll break it down into the following five categories and give examples, information I look for and rules of thumb I use regarding each category.

Hated

Intrinsic value

Cyclical

Sector analysis

Edge

Hated

While I'm not much of a technical trader, I do put a lot of weight on a bottom-crawling chart (straight from Brad’s playbook).

The bottom crawler contains a lot of information:

The majority of investors have lost money and have PTSD with the sector/company.

The majority have lost patience as the opportunity cost and FOMO have become too great, so they have moved on/chased something that is working.

This chart often represents a shake-out occurring in a sector/industry as it is starved of capital; those companies with excessive debt, bloated balance sheets and inefficiencies don't make it.

The flip side of this is that those companies that win the survival of the fittest are well-positioned to benefit when the tide turns for the sector (assuming it is cyclical).

The trick is finding companies and assets where your expectations and the markets are wildly different and that could converge on an acceptable timeframe (there is a big difference between being early and being too early).

“Being too early is indistinguishable from being wrong.”

-Howard marks

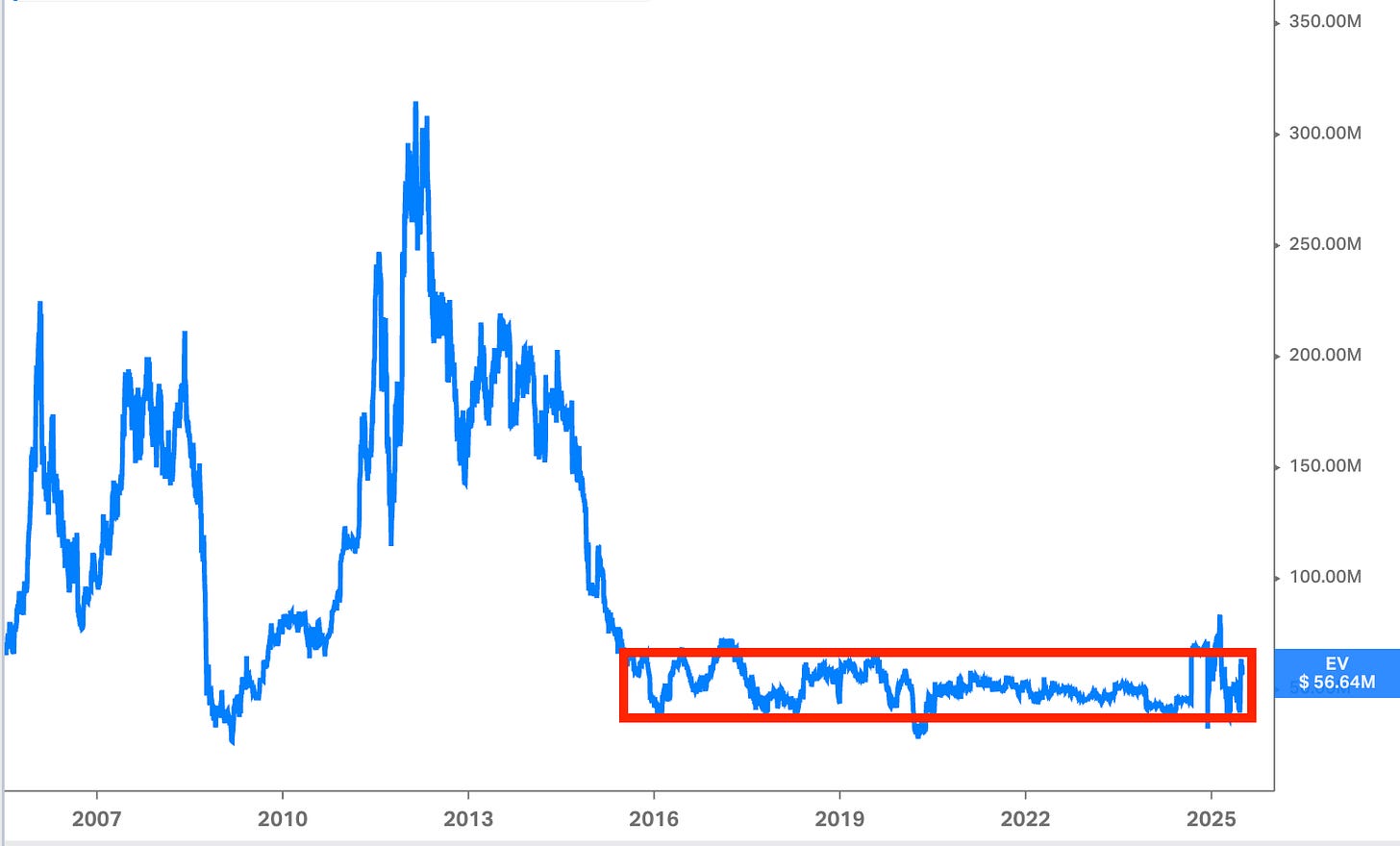

Here are some examples, be it enterprise value, market capitalisation, or straight percentage return. The two below should look familiar, as they are the last two positions I've brought!

Enterprise value (my favourite as it accounts for debt, cash and shares outstanding).

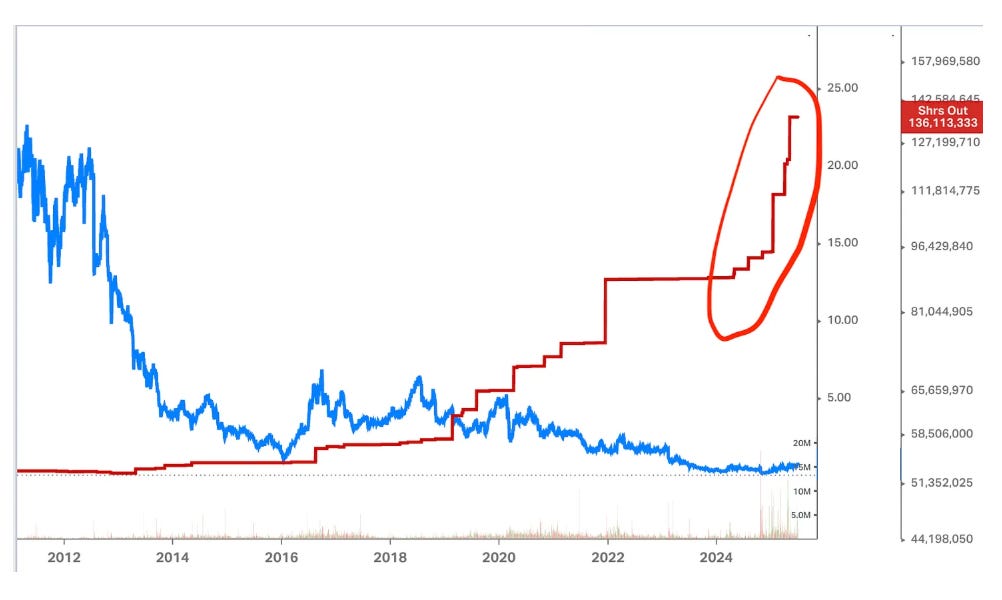

Market Capitalisation (next best metric for assessing long term charts)

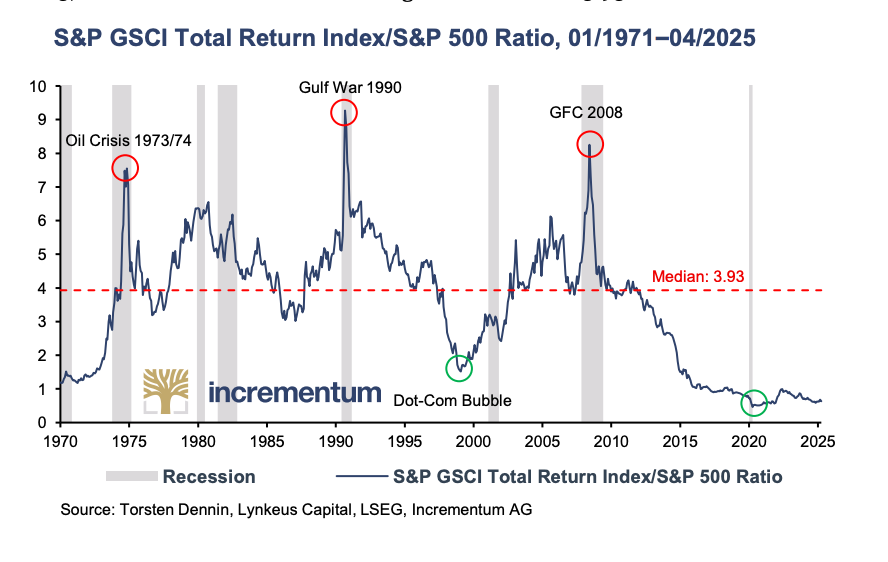

Percentage return (great for commodities).

A rule of thumb is that the longer and tighter the basing pattern, the larger the eventual breakout.

This is why I find the PGM space so interesting, as rhodium is in a crazy tight trading range, while platinum has recently broken out of a decade-long trading range.

When they break out of these trading ranges, the results can be dramatic.

Yes, these charts are just a starting point, as pointing to a few winners with this pattern leans heavily on survivorship bias.

There is a large graveyard of companies that go into Chapter 11 or have such large recapitalisation that they wipe out equity holders.

I've had the pleasure of partaking in both…

Below is Saipem, where I got wiped out, brushed myself off, and decided to buy in again.

The majority of long-term junior mining charts appear great until you realise they are actually call options, and the "time decay" being the rate at which they are printing shares.

It’s a race between dilution and value creation, with dilution usually winning.

Lastly, not everything is cyclical.

I'm betting heavily that commodities are cyclical.

In other areas, I'm not so sure, especially in technology. Take Xerox; you could be waiting a while for copier/fax machines to make a comeback and are betting on the company reinventing itself.

Intrinsic Value

The thing no one seems to care about anymore since they are too busy buying momentum and trading meme coins. Every time I thought we had reached peak stupidity, the bar would be raised, although the whole EtherRock JPEGs NFT still marked peak stupidity for me.

Focusing on intrinsic value is how I try to reduce the probability of having my ass handed to me.

Before I address intrinsic value, there is a list of no-nos for me, as staying at the table and avoiding ruin is always the number one consideration. As a result, I split risk into two baskets.

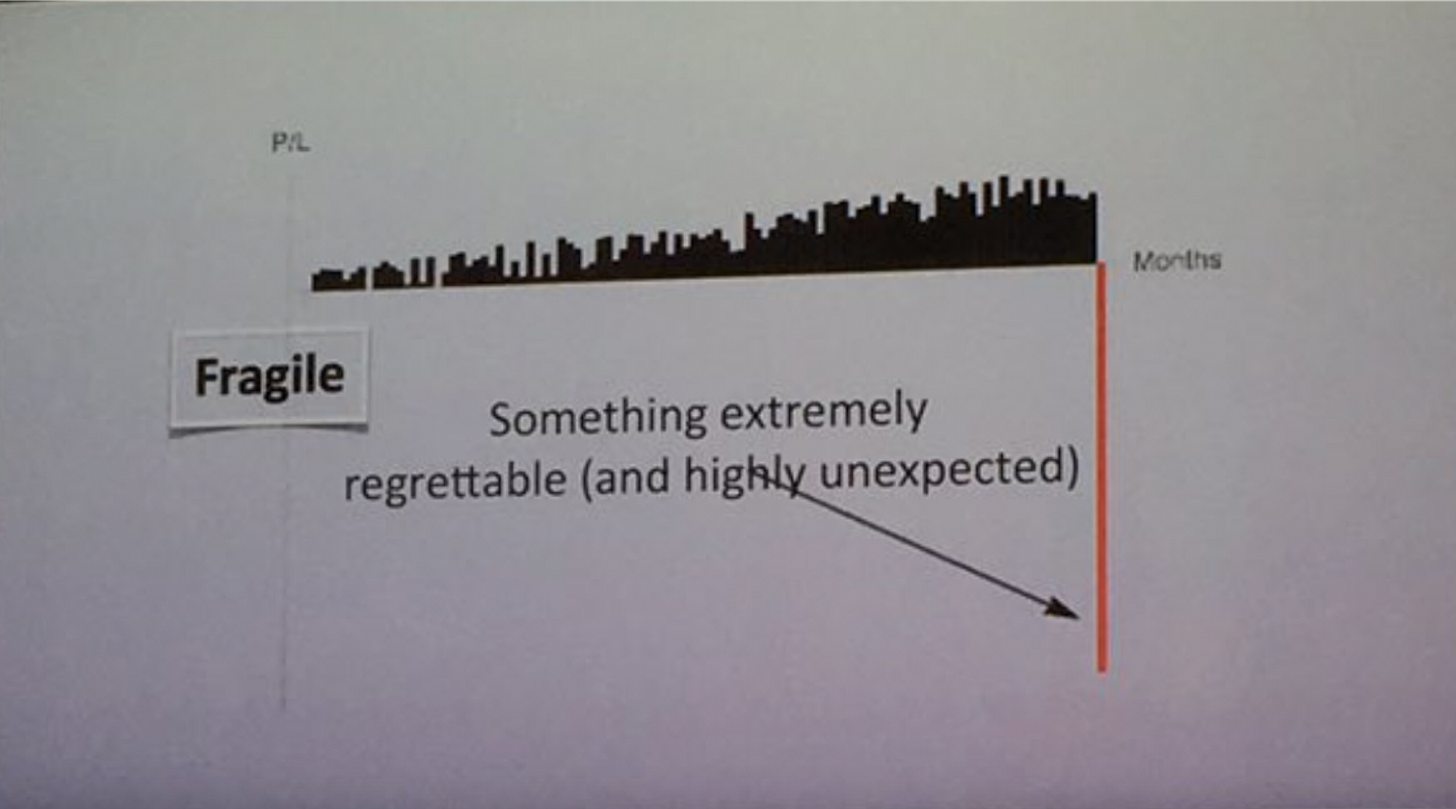

Known vs unknown risk

I want to eliminate unknown risks from my portfolio. A classic example is selling a deep out-of-the-money naked put.

Sure, it will be fine 99% of the time, but that 1% can blow up your portfolio.

Trading on margin, CFDs, futures, forex, and naked options are all no-goes with my approach.

I sleep well knowing there is no circumstance in which I can get a margin call.

Reading Fooled by Randomness by Taleb, and soon after seeing people lose their houses to relatively small forex positions on the Swiss Franc de-peg (January 2015). Then in a nasty twist of fate, my first brokerage account got wiped out anyway with my broker, BBY Australia, going into liquidation in May 2015.

I can laugh about it now, but I certainly wasn’t laughing about it back then!

More recently, the entire GameStop saga serves as a reminder of how badly things can go when one gets caught on the wrong side of extreme optionality/asymmetry like Melvin Capital did.

Known risk

Recognising that my maximum loss is 100% of my capital invested in a position is a known risk, I size the position accordingly.

Position sizing is a balancing act between risk minimisation and regret minimisation.

Risk minimisation

Next is keeping the position size small so that no single position can harm the portfolio, i.e., 1% per position.

For the maximum position size, it pays to remember that math makes it easy for large positions to damage portfolios, i.e. 50% loss requires a 100% gain to break even.

Regret Minimisation

The other side of this coin is the opportunity cost of being too safe (which rarely gets discussed). Regret minimisation is ensuring positions are big enough to make a difference to the portfolio.

1% position becomes a 10x = 10% gain.

5% position becomes a 10x = 50% gain.

An interesting anecdote related to this is Benjamin Graham's statement that investors should hold no fewer than 30 stocks in their portfolio. His philosophy was based on minimising as much downside risk as possible.

Yet Graham, on reflection, had the below to say.

“Graham wrote Security Analysis in 1934 and had started training some of the sharpest investing minds to do the same. The fact that, nearly 40 years later, at the age of 79, he mentioned that he did incredibly well over his last two decades with an initial bargain that became a 200-bagger doesn’t damage, or even dent, his value legacy. The aggregate profits from their partnership’s investment in Geico alone exceeded the sum of the gains in all other positions that partnership held over the previous 20 years.”

Or to quote Lee Freeman-Shor from one of my favourite investing books in the Art of Execution.

“The most successful investors I worked with, those who made the most money, all had one thing in common: the presence of a couple of big winners in their portfolios. Any approach that does not embrace the possibility of winning big is doomed.”

Replacement Cost

When I refer to intrinsic value or margin of safety, it typically means buying something at a price well below its replacement cost.

Can I purchase this commodity, drillship, OSV, or mine at a discount compared to the future replacement cost?

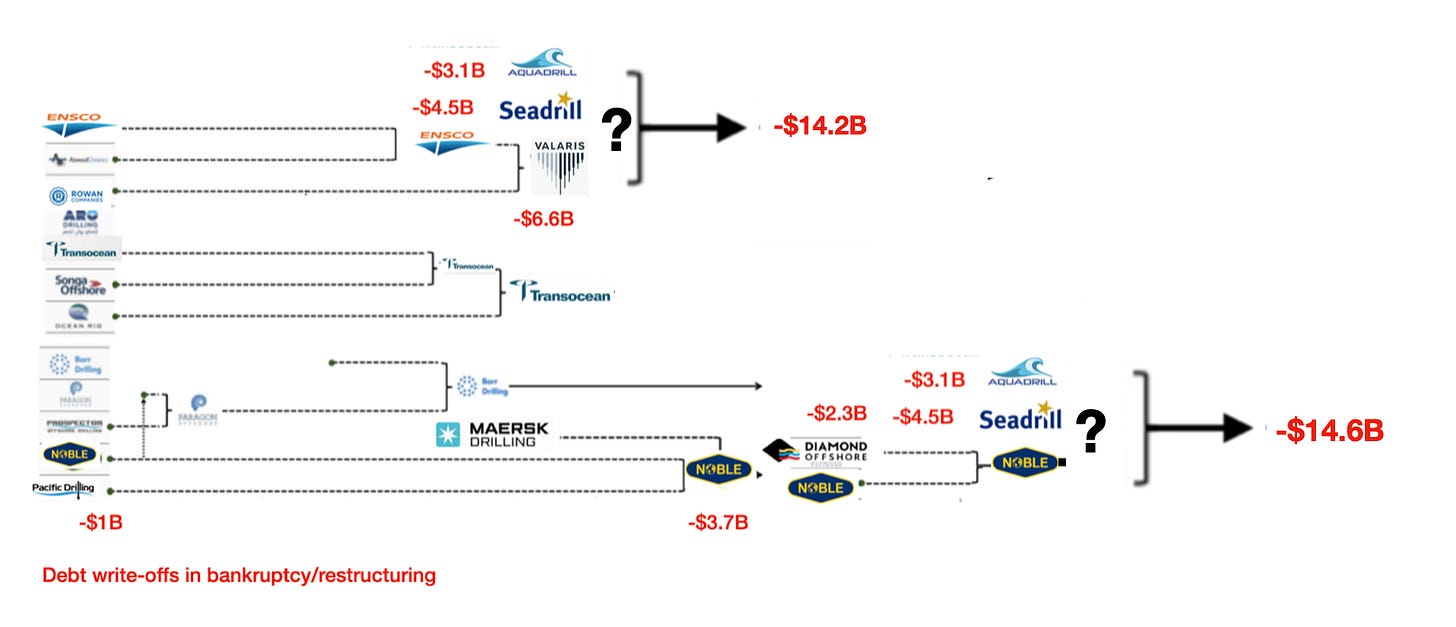

The offshore drillers are the group with the largest discount to replacement cost I own due to the multiple bankruptcies. For most of these companies, you can buy rigs for less than a quarter of their replacement cost. A cost that will likely be substantially higher by the time they are incentivised to start building them again.

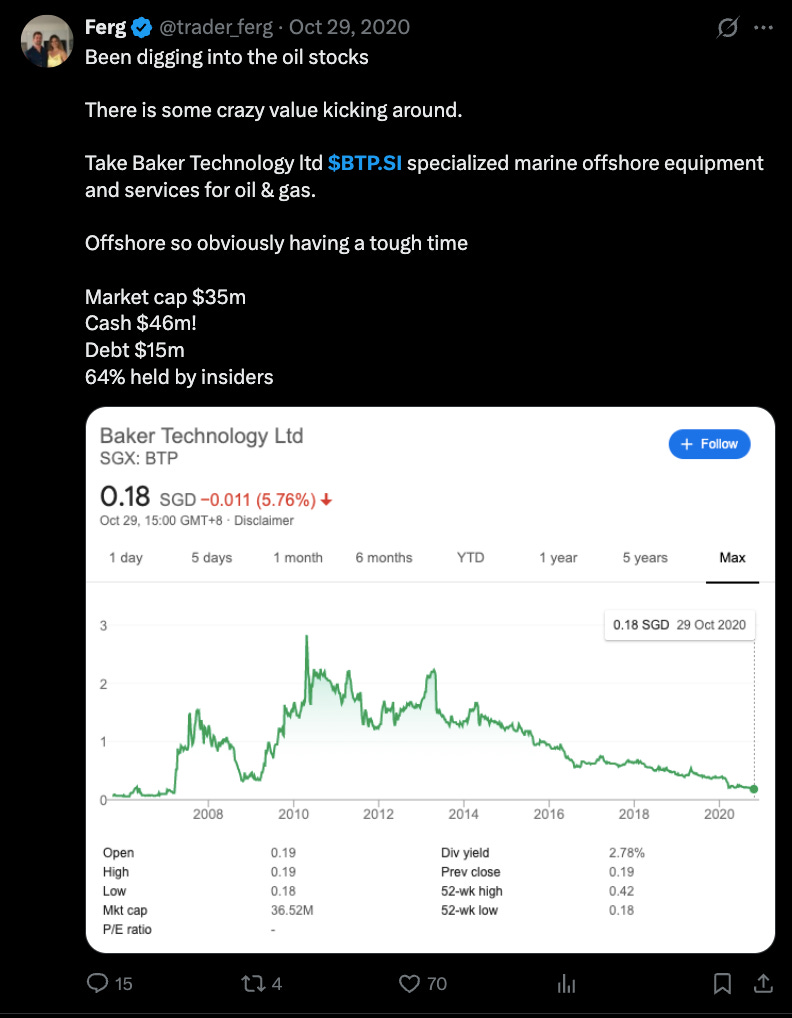

Cash

A margin of safety can simply be cash; here is a tweet from October 2020, where I didn't have a strong view on the company but figured it was hard to screw it up, given the company's majority cash position and its underlying offshore equipment business, which is quite cyclical.

Cashflow

Cheap cash flow provides its own margin of safety.

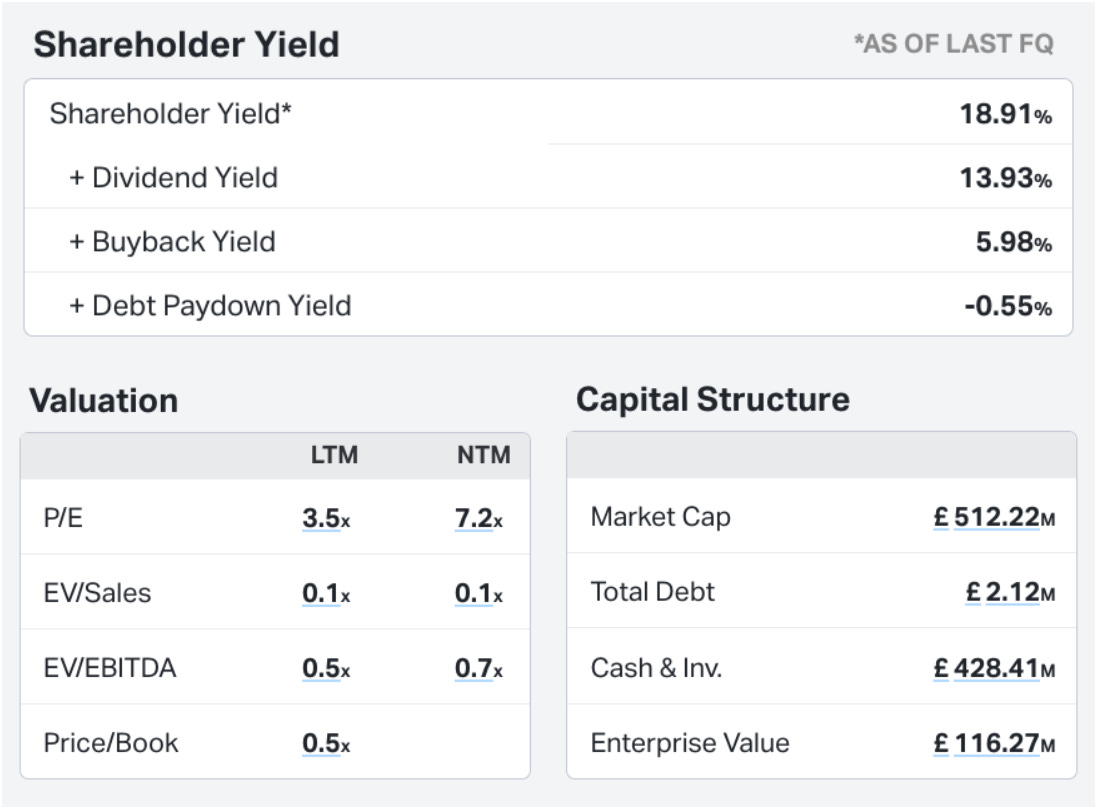

Below is a coal company I own, and while coal prices have been in the toilet lately, I can still pencil in a double on 3-4 years based on reinvesting the dividend and the buyback alone. Not to mention the company's market cap is 83% cash. Coal prices do well over this period. But I'll be fine if they don't.

I loved Ian Cassels' quote below, as yes, I can come up with bullish scenarios, but how will things look with a conservative or even pessimistic outlook? If they still look good, then odds are heavily in your favour!

To find a 10-bagger first find a stock that can double in three years with conservative fundamental assumptions and no multiple expansion.

Granted, the cheap cash flows you get with coal (particularly thermal) are quite unique, as few are prepared or allowed to own thermal coal companies.

My strategy for this has been understanding the cyclicality of many of these companies' earnings and trying to pick them up when they make their first bit of profit while the review mirror still looks grim (below is the last company I bought, which illustrates this idea well).

Cyclical

Identifying something is cyclical isn’t hard, identifying where you are in that cycle in a actionable way is hard!

We can make excellent investment decisions on the basis of present observations with no need to make guesses about the future.

We never know where we’re going, but we sure as hell should know where we are.

-Howard Marks

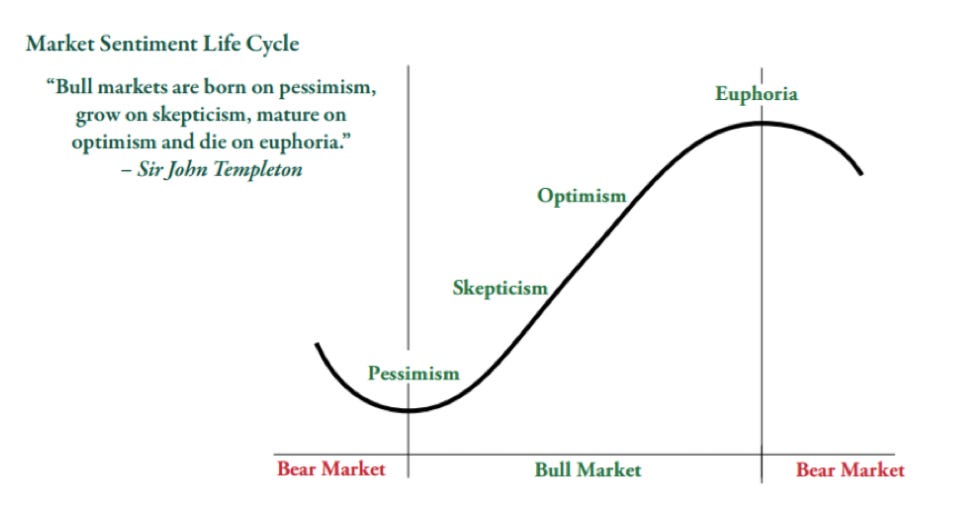

Knowing where we are regarding sentiment is more art than science. My metric for measuring sentiment has always been Sir John Templeton's maxim.

Whats a example of peak pessimism?

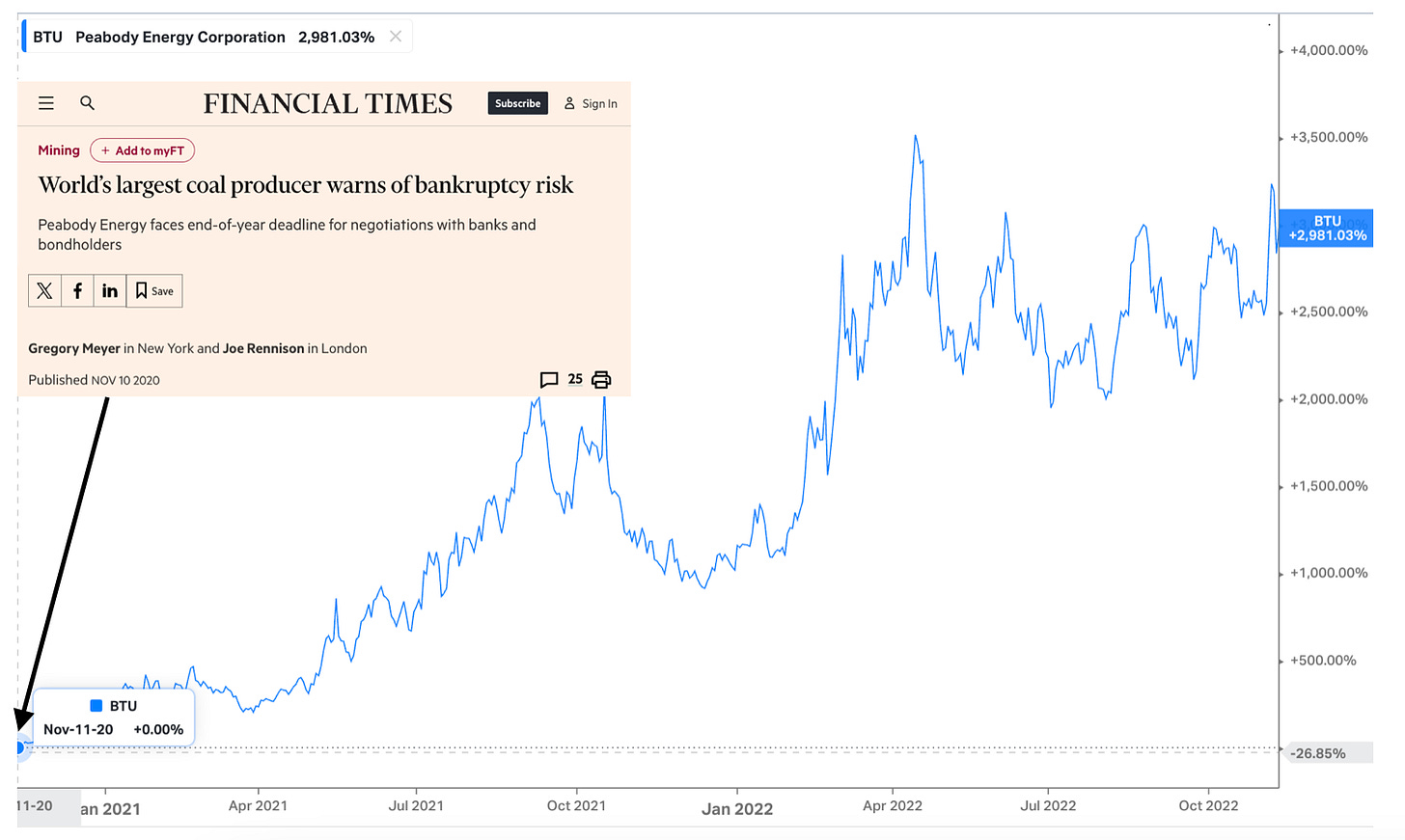

Coal in late 2020 is a good example of what peak pessimism looks like, with back to back contrarian signs:

World’s largest coal producer warns of bankruptcy risk. 10th November 2020

Anglo American completes demerger of Thungela thermal coal business 7th June 2021

How about peak euphoria?

Peak euphoria is only knowable after the fact, and is a fool's game to call tops in markets. You can observe that something is unsustainable, but that in itself doesn't mean it will end anytime soon.

Morgan Housel puts it well,

"You can measure everything about a bubble except the most important part: When investors will stop believing in it. The end of the bubble is just the end of enthusiasm. And enthusiasm isn’t a tamable statistic. It’s a hormone that owes nothing to the logic of your data."

What are examples today?

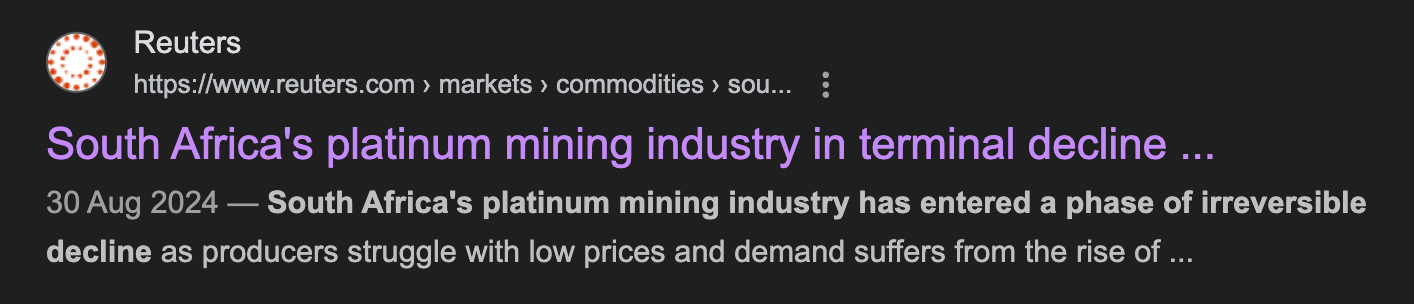

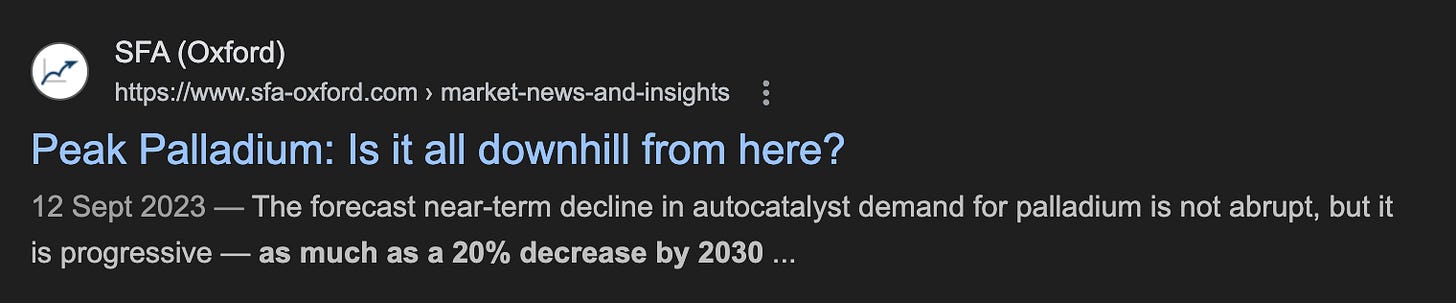

PGMs may have taken off lately, but if you rewind a few months, sentiment was pessimistic.

Oil and offshore oil services

Easily the most pessimistic outlook today has to be oil and offshore in particular. The only offshore oil ETF closed down after a year, and according to the IEA, the supply glut and demand peaking mean offshore rigs, OSVs and oil services are toast.

While the IEA may have walked back the below statement, the damage has already been done with underinvestment over the past decade.

"There is no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply in a Net-Zero pathway to 2050".

-IEA May 2021

Peak pessimism is essentially saying that the market has run out of sellers, as everyone who was going to sell has already done so.

"It's best to think of financial markets as examples of mass human behavior"

-Paul Singer

Or if you'd prefer a visual.

Sector Analysis

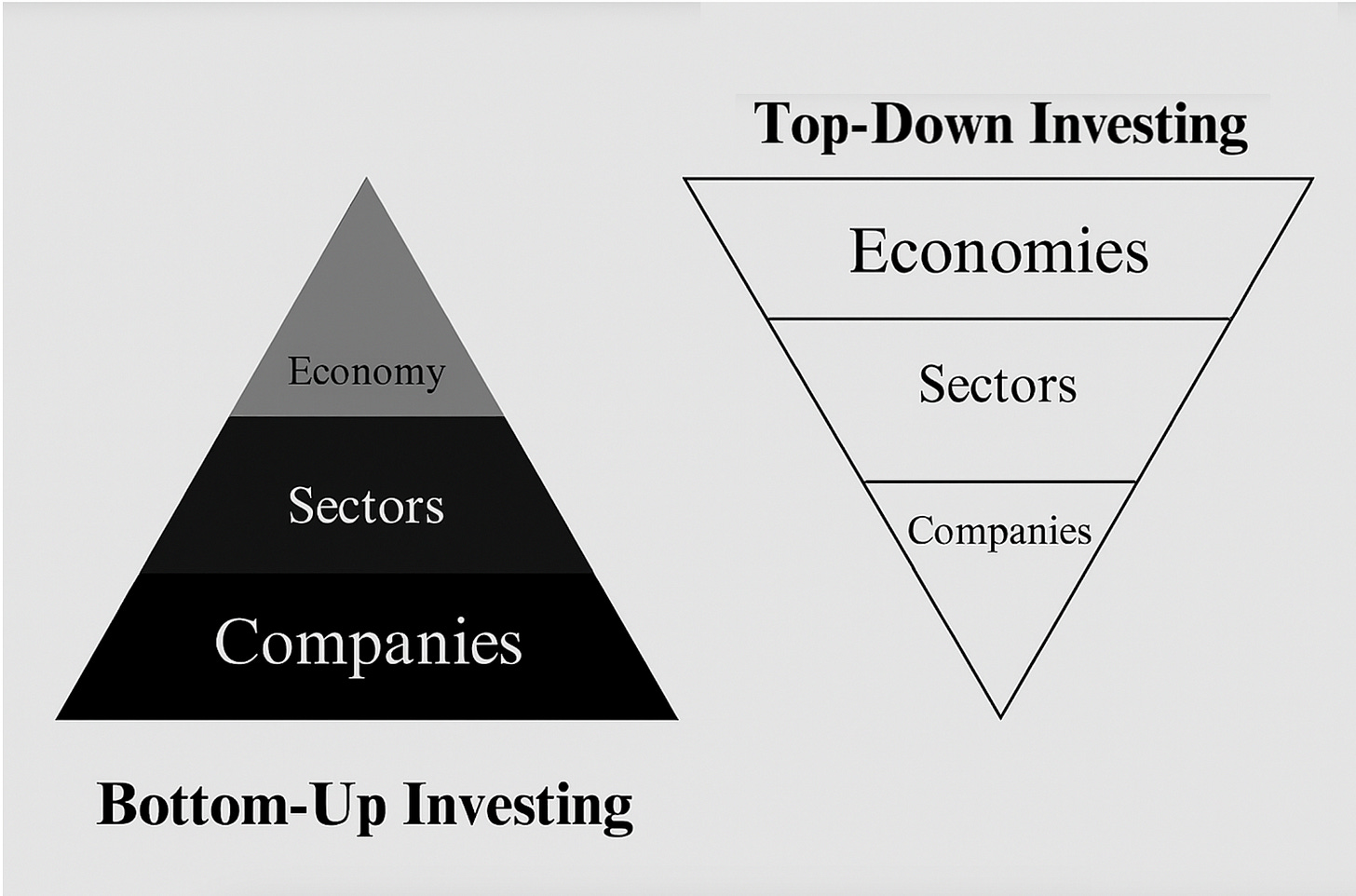

Investors orient towards their preferred style of investing, be it top-down or bottom-up. I find pure top-down/global macro investing challenging because there are too many variables at play in economies. At the other end, ignoring it in favour of mainly focusing on the companies seems fraught with danger, as it doesn't matter if you were the best offshore driller analyst in the world in 2015…

For me, it's more of a diamond shape, with the sector getting the heaviest weighting.

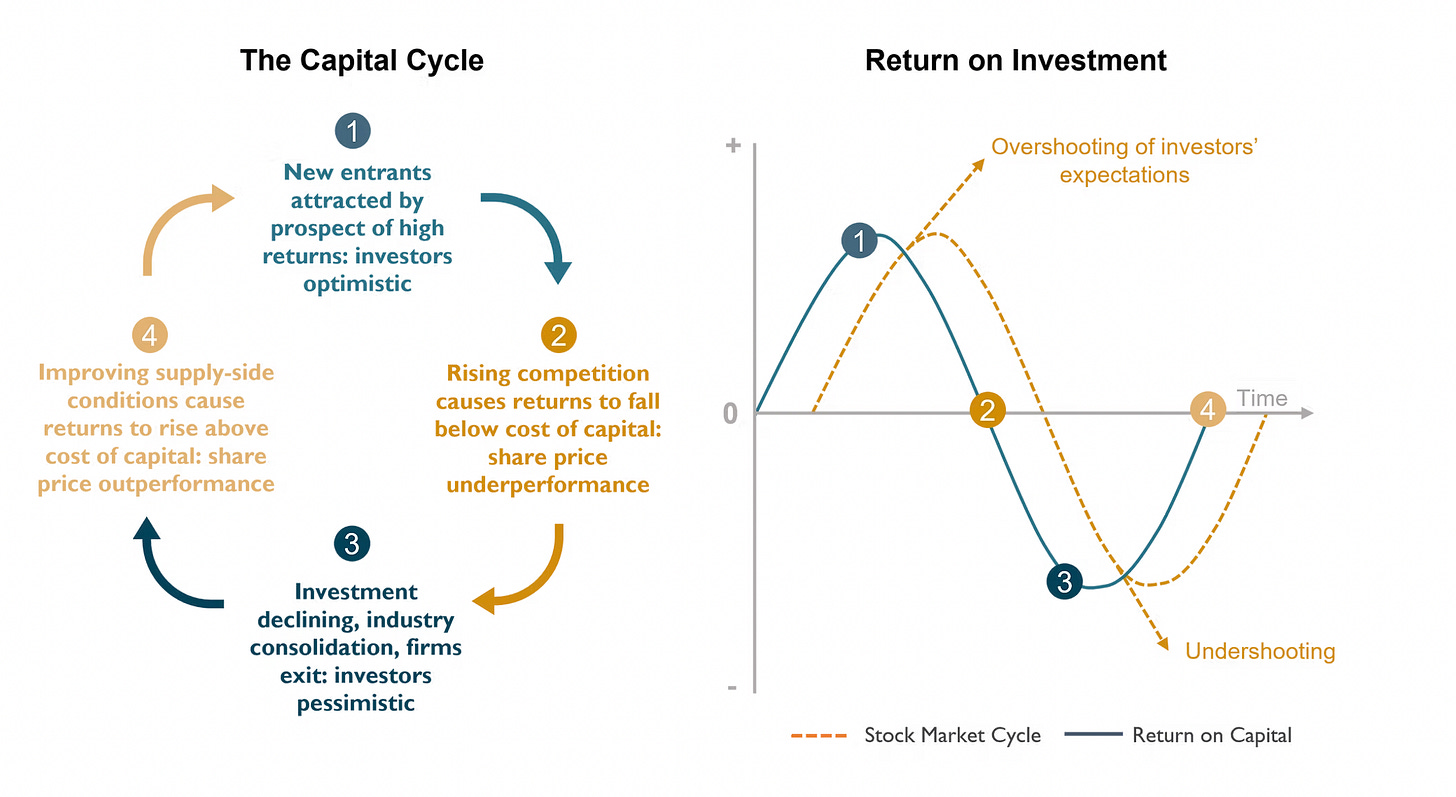

The simpler the sector, the better, as it makes it easier to work out where we are within the particular sector's capital cycle and, obviously, ties into sentiment, which is expectations overtaking or undershooting.

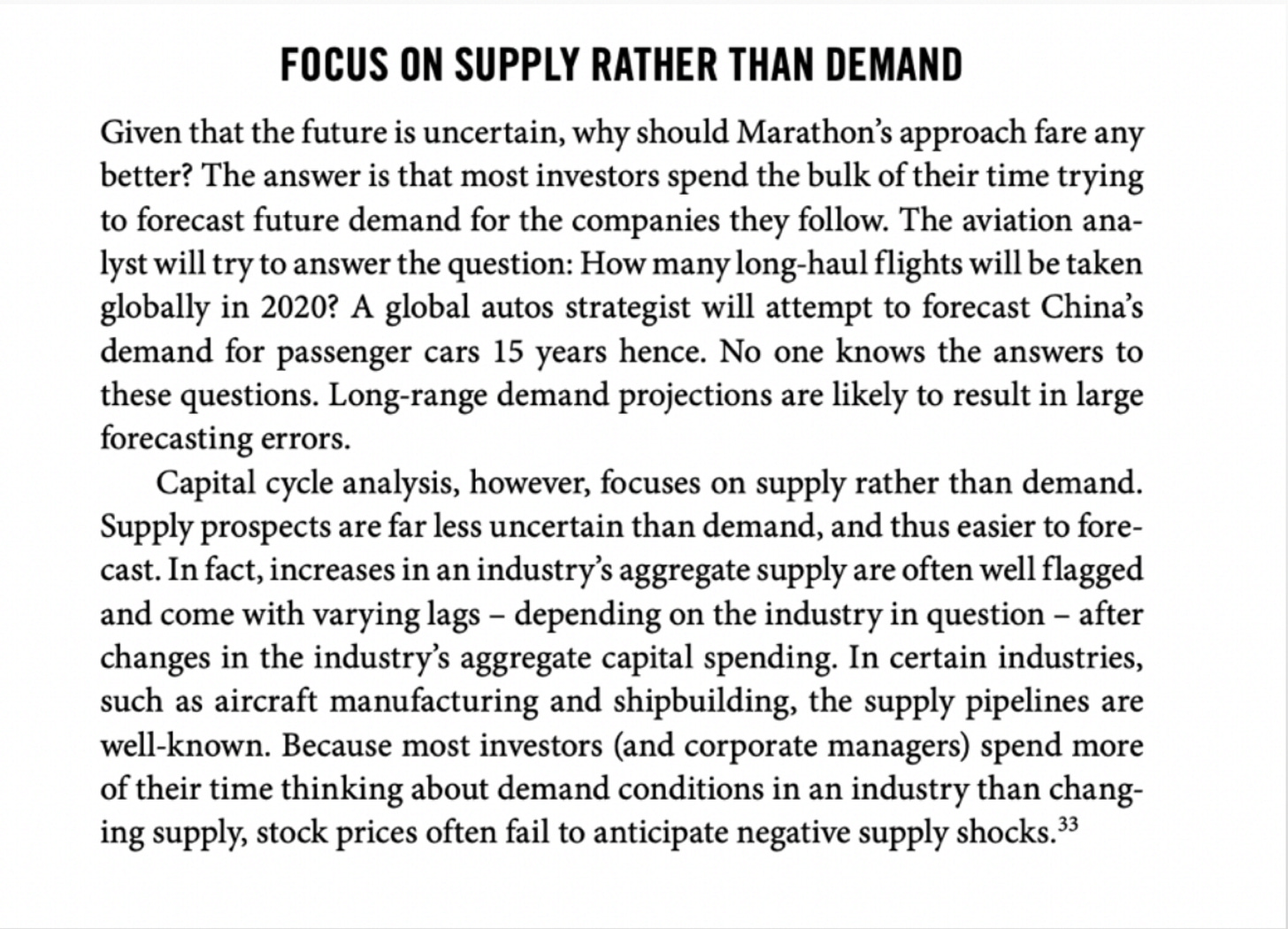

The focus is on supply as it's a slower-moving beast, and far easier to hit than demand, as Marathon outlines here:

What is an example?

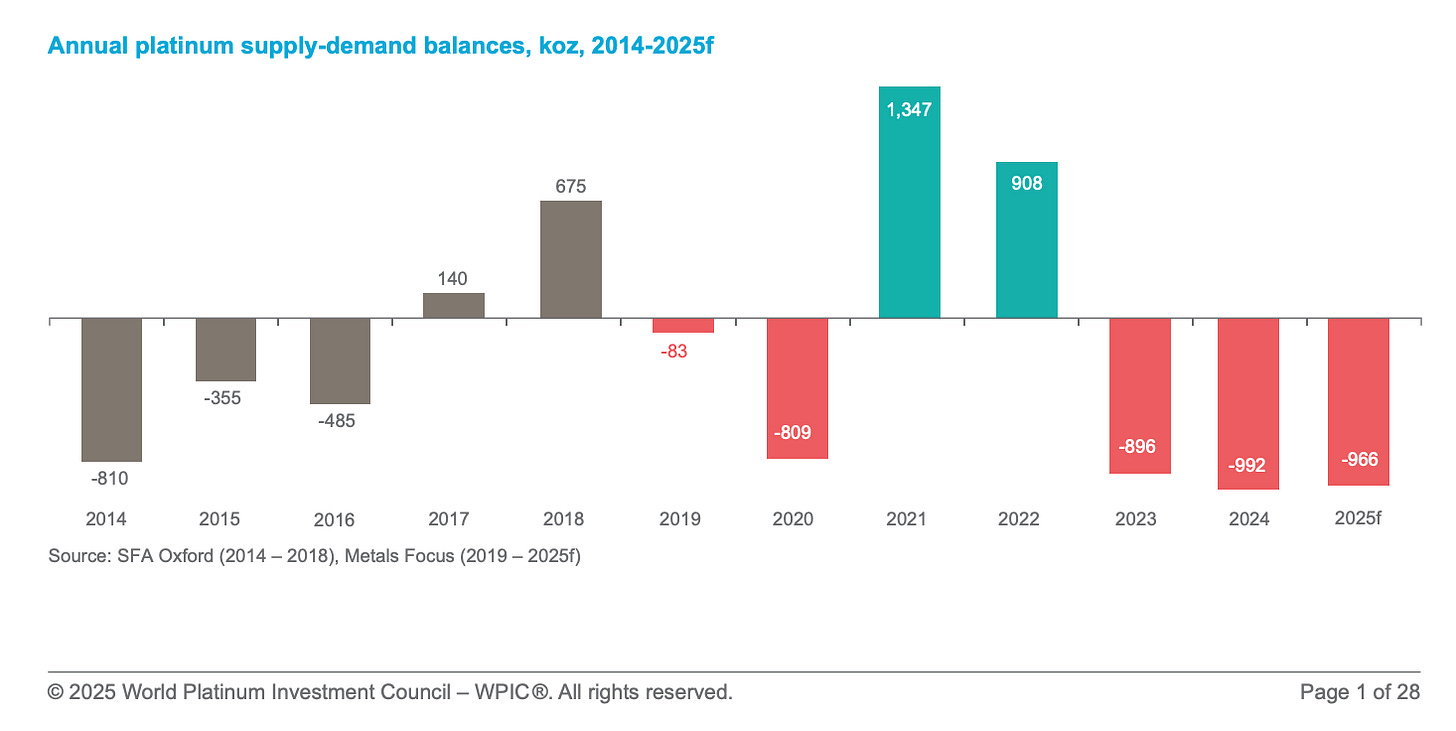

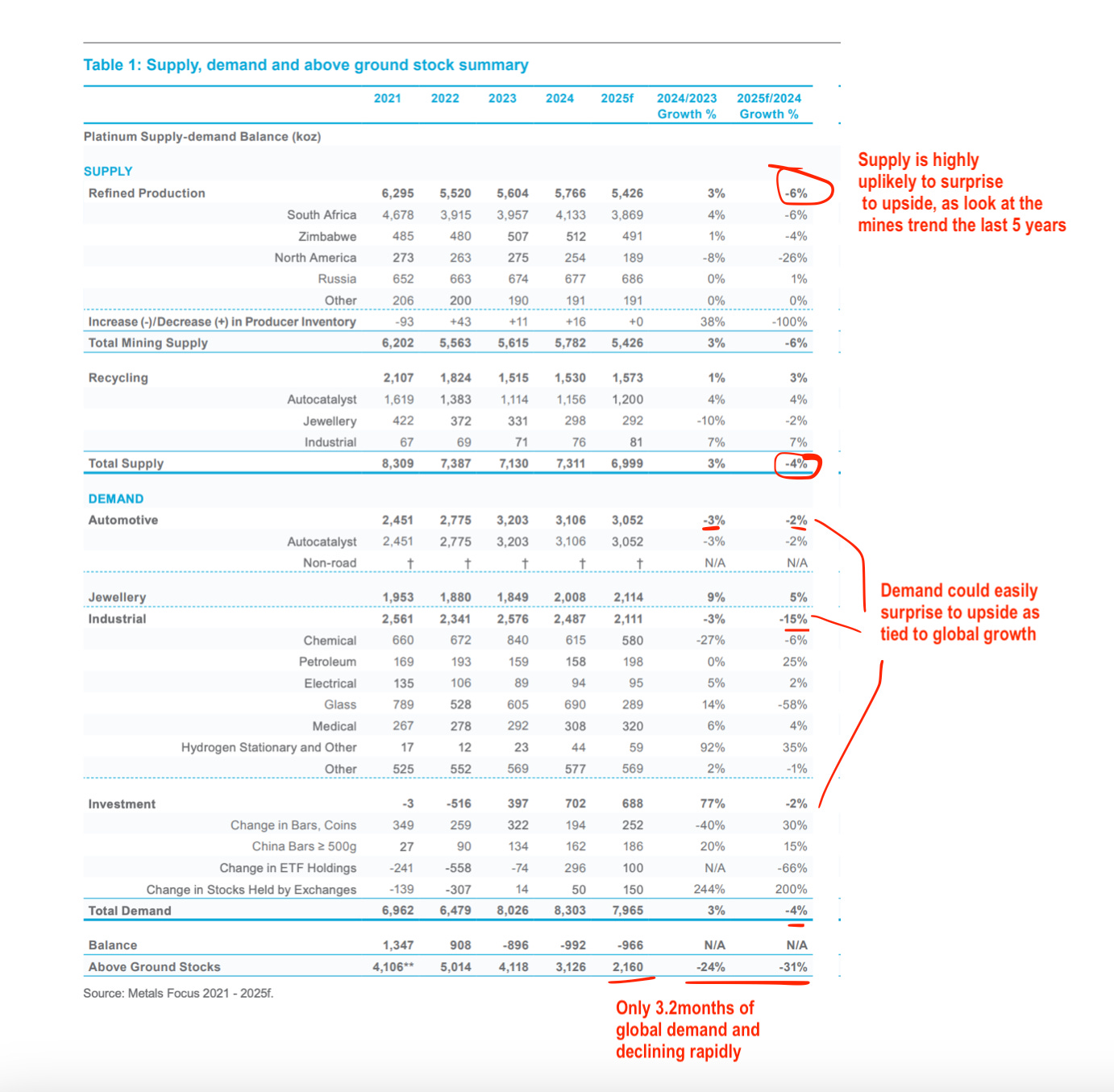

The World Platinum Investment Quaterly Q1 2025 painted a hugely bullish picture for anyone who took the time to read it.

There was a line in it which jumped out at me:

Total platinum demand is forecast to decline by -4% year-on-year in 2025 (-338 koz) and with a projected market deficit of 966 koz. Given compelling market fundamentals, a severe and sharp deterioration of economic conditions would be required to materially reduce entrenched supply shortfalls, which seems unlikely.

Translation: if anything goes right at all, the price is going to fly!

Lastly, while it's not information you can seek out, understanding where your edge lies in the market is vital if you are to maximise it.

Timeframe

Illiquidity

Volatility

Incentives

Risking Embarrassment

Timeframe/Patience

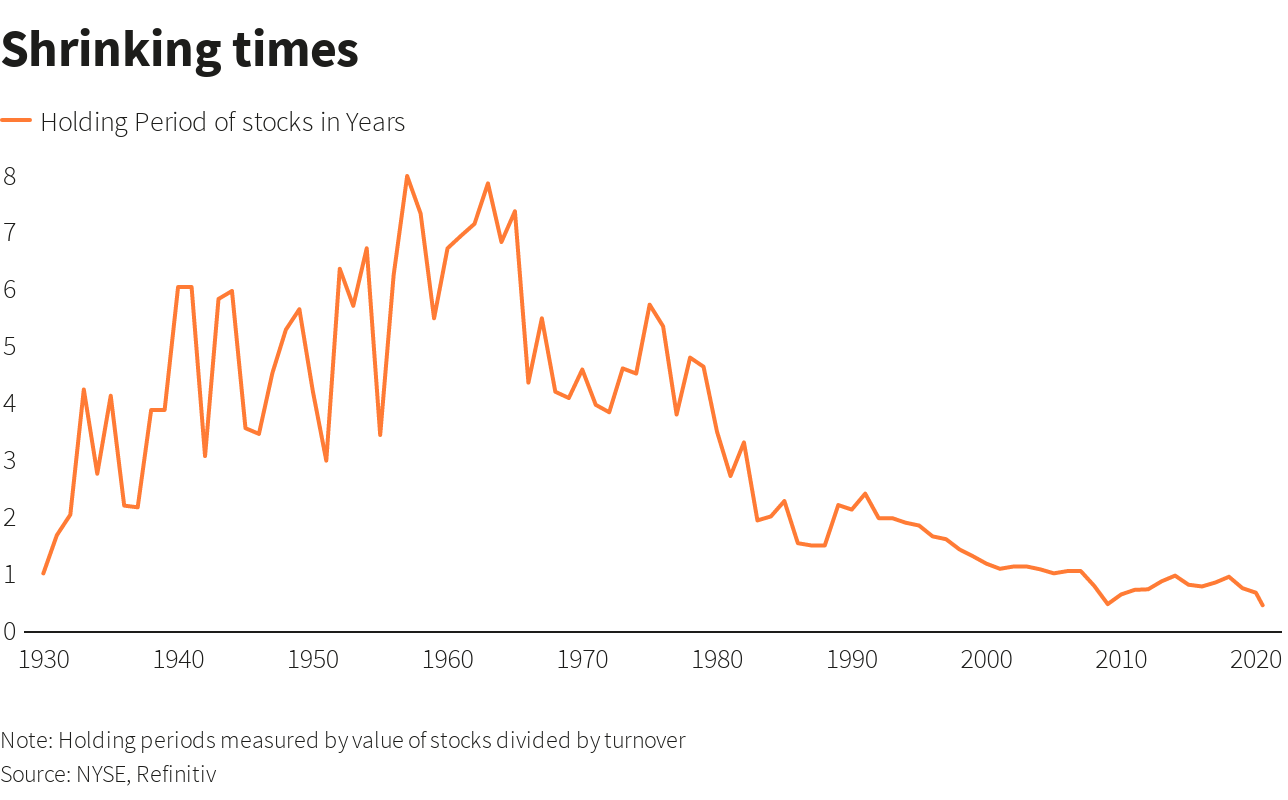

I don't recall where I first heard it, but the way to combat high-frequency trading and algorithms is through low-frequency trading and extending the timeframe.

Which is the opposite of what the average investor is doing today with average holding getting as low as five and a half months in 2020.

One of the largest advantages of being a retail investor is that you can expand your timeframe and not worry about quarterly reporting, redemptions, or if the thesis takes longer to play out than you anticipated, which almost always happens!

Jason Zweig said it best.

“Approximately 99% of the time, the single most important thing investors should do is absolutely nothing.”

Take platinum, where very few fund managers would still have their jobs holding platinum, as it did nothing for a decade while US tech shot the lights out.

Stomaching Volatility

My favourite illustration of this idea remains this study by Wesley Grey.

Even God would get fired as an Active Investor

Perfect foresight has great returns, but gut-wrenching drawdowns. In other words, an active investor who was clairvoyant (i.e. “God”),(1) and knew ahead of time exactly which stocks were going to be long-term winners and long-term losers, would likely get fired many times over if they were managing other people’s money.

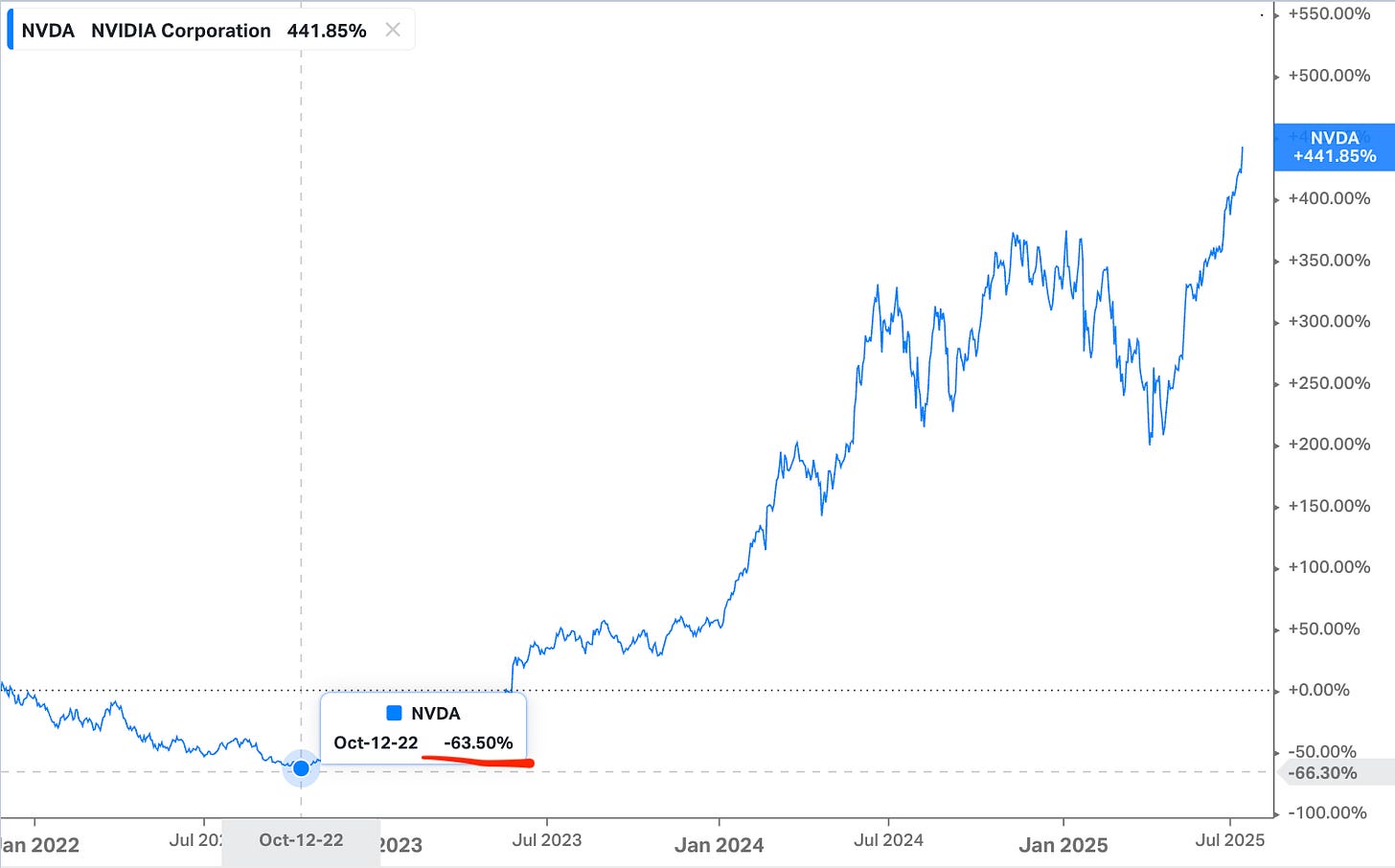

It's all so obvious with hindsight bias, but consider someone who bought Nvidia early in 2022 was staring at a ~60% drawdown by October.

There will be no shortage of these examples across the commodity space, with people quick to forget how much it sucks being at that point in time with a 60% drawdown and your emotions screaming at you to hit the sell button before it goes to zero!

There will be no shortage of these examples across the commodity space with people quick to forget how much its sucks being at that point in time with a 60% draw down and your emotions screaming at you to hit the sell button before it goes to zero!

Illiquidity

This one is self-explanatory when you go sub $300m market caps, the big money can't follow. My most recent purchase was a nano-cap, and it's where I'm seeing the craziest bargains at the moment.

Risking Embarrassment

Risking embarrassment is an edge, in a similar fashion to buying a way out of the money call or put option, you are going to be wrong the majority of the time.

Take this quote from Jeff Bezos:

'Given A 10% Chance Of A 100x's Payoff, You Should Take That Bet Every Time'

While he is right, a few money managers want the embarrassment of buying something that potentially goes bust the next month… The embarrassment/career risk is a greater danger than missing the payoff.

Example?

While I'm not managing money, I personally had this with Peabody Energy. I remember staring at it below a dollar and couldn't pull the trigger. I bought it when I figured it was "safe" at the end of December, after it had traded up to $2.70 (from a low of $0.77).

The point of this isn't woulda, shoulda, coulda, stories which everyone has, the point that annoys me is that I paid 350% more just over a month later to be "safe". I could have risked 1% and ended up nearly with my eventual position size of 4% instead of having to come up with all that extra cash…

Incentives

“Never, ever, think about something else when you

should be thinking about the power of incentives.”

-Charlie Munger

It's no secret that retail ends up the bag holders in markets.

IPO's are events for insiders to use retail for exit liquidity.

The same is about to happen with retail, "finally gaining access" to private equity.

What to do about this?

Be highly sceptical of anything being pitched to retail by Wall Street.

My favourite areas to hunt are:

Go where the big boys can’t (micro and nano-caps)

Spin-outs

Relistings

Index deletions

Exotic markets.

Go where the big boys can’t

Well, back to my earlier point: if you get involved in a nano/micro cap that does well, you enjoy the flywheel effect of it achieving sufficient liquidity for the big boys to join the party and eventually get added to indexes.

Spin-outs

There is a long history of companies being spun out from their parents, going on to outperform them substantially, especially when the spinout is not based on economic considerations, i.e. Net Zero ideology. We have seen this repeatedly over the last few years with mining majors spinning out their "dirty" assets to focus on "transition" metals. To date we have seen and I expect to continue to see massive outperformance by the assets that are spun out.

Relistings

One of my favourite angles in the market is to set Google alerts on cyclical companies I see go into Chapter 11/bankruptcy.

When a company goes bankrupt, the original equity holders usually get wiped out, while the debt holders accept a debt-for-equity swap and have an incentive to see the company succeed when it is relisted, so that they can recoup their investment. On top of this, the companies themselves are usually in far better shape, having eliminated a large proportion of their debt.

Index deletions

I haven't used this much in my investing, but it's a good angle to know.

A key study conducted by Research Affiliates found that stocks taken out of the S&P 500 between 1990 and 2022 outperformed those that were added by over 5% annually in the five years afterward.

Exotic markets

The harder it is to get access to via brokers, the less likely it is to be affected by volatility in the broad markets.

I noticed this in the liberation day sell-off since I have some positions that were a pain in the ass to get my hands on, but as a result, they are highly uncorrelated to what global equities do.

It takes effort, but opening brokers to get access to Sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, i.e. Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, etc, is a real edge.

You might think there would be a high opportunity cost to being outside the large global capital flows?

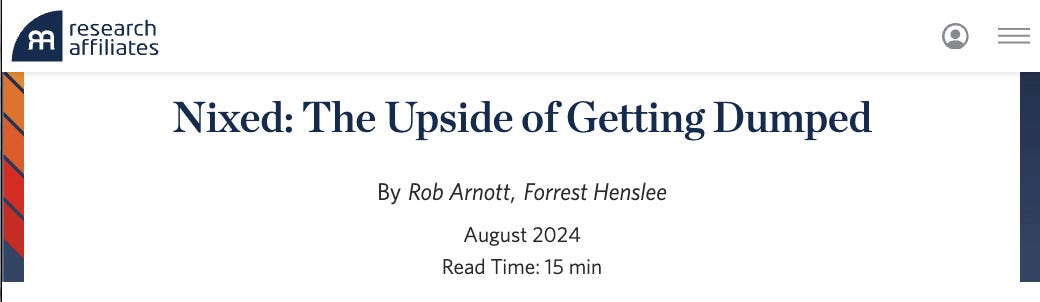

One that may surprise you is the crazy performance of some emerging indexes.

Here is the Hungarian BUX and Warsaw exchange, which has crushed the Nasdaq since their launch.

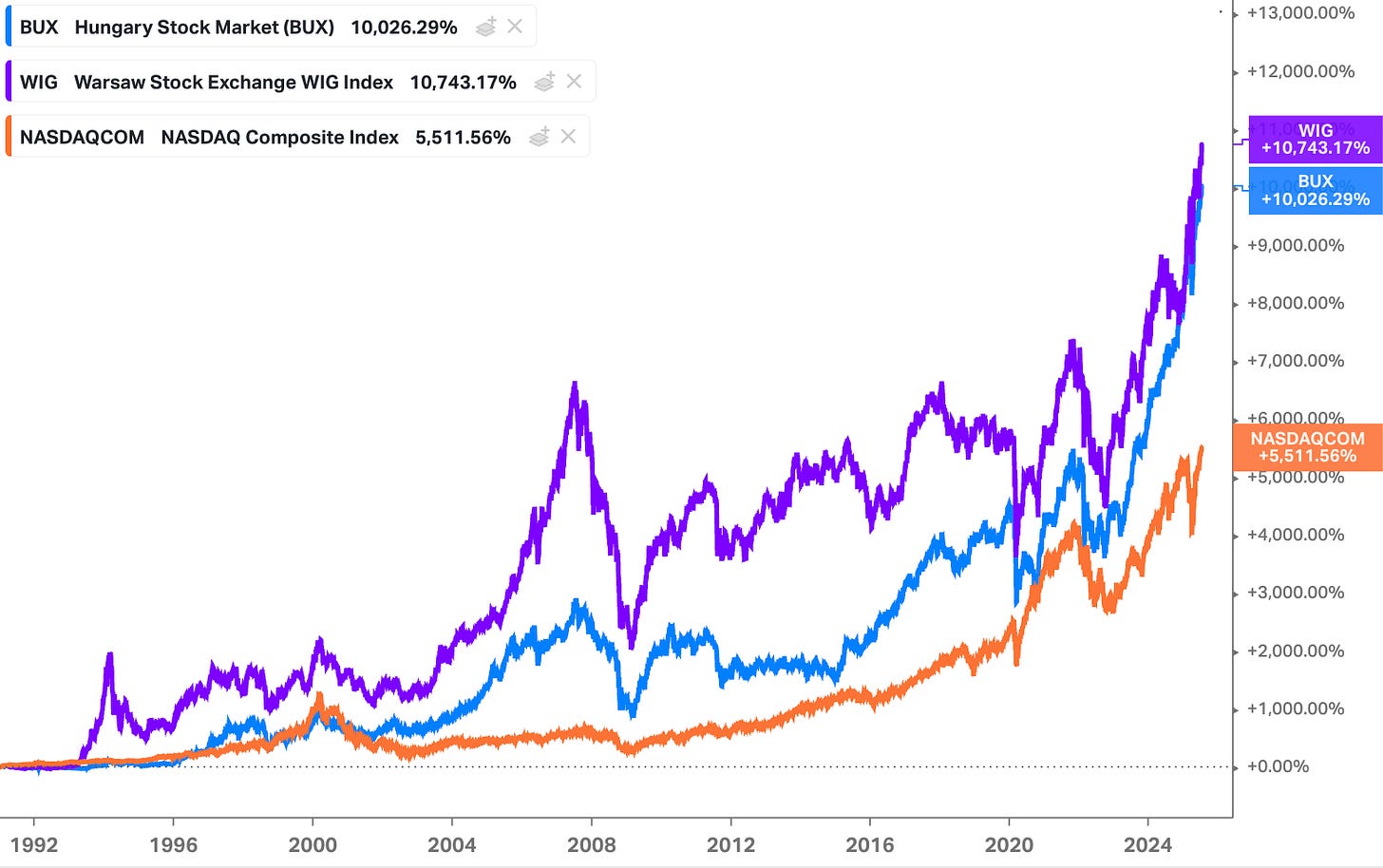

What about currency and accessibility?

With the Hungarian BUX adjusting for currency depreciation (USD/HUF averaged ~150 in 1992; by 2025 it's 340), so the 100× HUF gains translate to ~50× in USD. You also had to put the index together yourself up until 2006 when the first BUX etf was created.

The Warsaw exchange is the crazier one, as you could have taken home that return, since the USD/PLN was ~3.3 in the mid-1990s and ~3.65 in mid‑2025, so only 10% depreciation reduces returns from 107× to ~97× in USD.

Update: Warsaw exchanges performance isn’t nearly as impressive when take into account this period of currency depreciation (which I’d missed with the above).

Cheers,

Ferg

P.S. A bit of housekeeping: I've paused paid subscriptions on my Substack while I restructure a few things in the background. It should only be back up next week hopefully, but for now, no one new can subscribe to paid tiers. For paying subscribers, your current subscription will be extended (for free) by the period I've paused payments for.

That was a great read. "Minimum effective information" is the one I discovered/realized for myself recently. Particularly in uranium I feel I almost dug too deep and built such a strong conviction for the long term ultimate outcome that it made me too rigid in the way I've been playing this thesis. Meanwhile I've got no such difficulty in other sectors I did less DD on and it helps me manage these parts of the portfolio better.

Funny how human mind works

Great write-up. Should I reduce my Xerox position? 🤣