I've always approached the market from the viewpoint that most things prove to be cyclical, and the exceptions to this, such as Moore's Law, are still made cyclical by humans' investing behaviour (greed and fear).

Embracing the cyclical nature of markets is the only way I know of to make outsized returns since it involves arbitraging human behaviour and impatience, which are two edges I don't see disappearing any time soon.

Making predictions is a mugs game, but understanding where you are in the cycle and the likely future outcome is a different story.

In my opinion, the key to dealing with the future lies in knowing where you are, even if you can't know precisely where you're going. Knowing where you are in a cycle and what that implies for the future is very different from predicting the timing, extent and shape of the next cyclical move. And so we'd better understand all we can about cycles and their behavior.

-Howard Marks

It’s all about positioning for where you see things in the coming years. If you're thinking five years out, few institutions, funds, and retail investors can hold investments within that timeframe due to quarterly performance reviews or just sheer impatience.

Ray Dalio has a great piece I recommend you read called: The Changing World Order: The New Paradigm and this earlier version (Paradigm Shifts).

Paradigms typically last about 10 years, with occasional big corrections within them. They are driven by a persistent set of conditions that takes those conditions in a swing from one extreme to an opposite extreme. Because of this, each paradigm is more likely to be opposite than similar to the one before it.

For example, the Roaring ’20s were followed by the depressionary 1930s, and the inflationary 1970s were followed by the disinflationary 1980s. The assets and liabilities that you would most like to have, and those that you would most like to avoid, change with the paradigm that exists at the time. For example, in the Roaring ’20s you’d want to own stocks and avoid bonds, while in the depressionary 1930s it would be the opposite; in the inflationary 1970s you’d want to own hard assets like gold and avoid bonds, while in the disinflationary 1980s you’d want to own financial assets and avoid hard assets.

It will come as no surprise. I believe we are in for a highly inflationary decade, during which the investment focus will shift from finding growth in an easy-money, low-inflation environment to protecting and creating an adequate return despite high inflation.

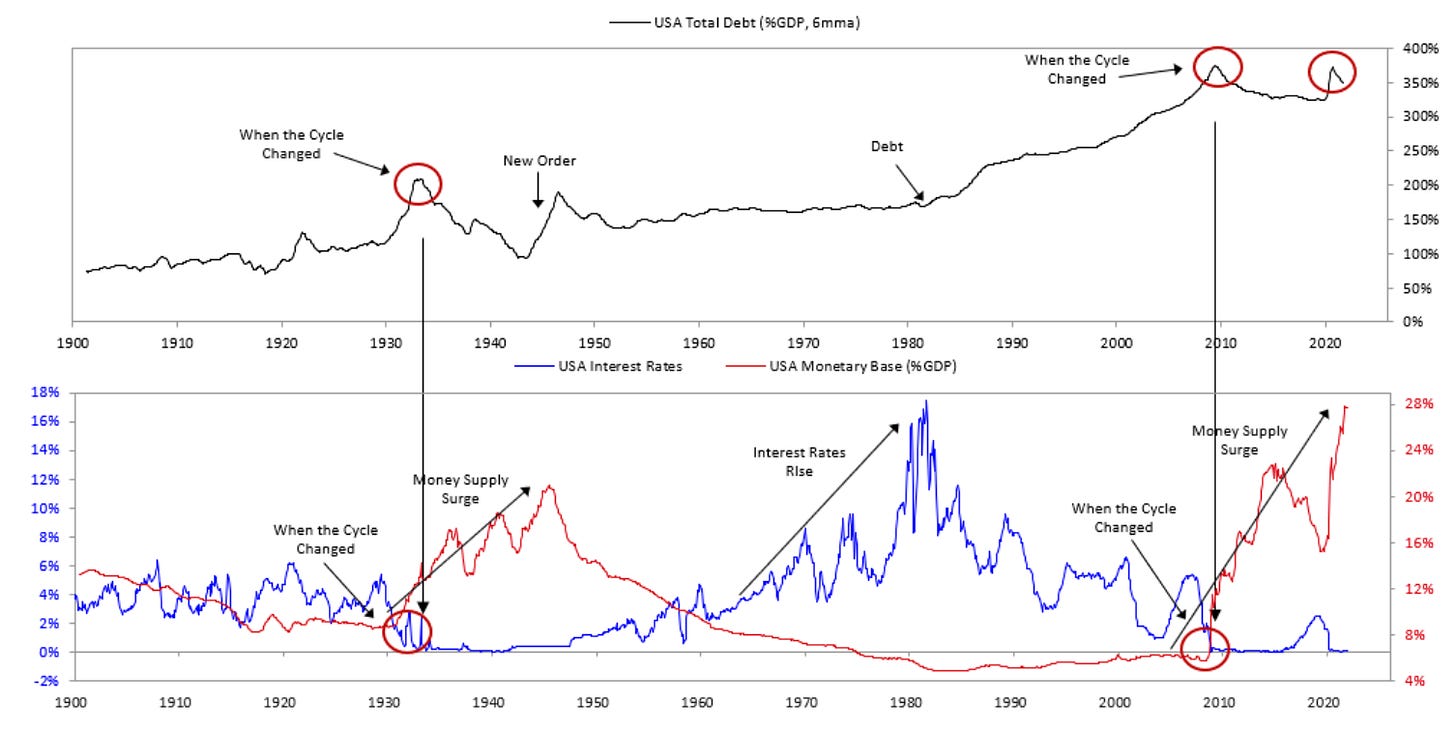

This isn’t a hard conclusion to arrive at when you consider there are really only three ways out of the current debt situation the US finds itself in.

Austerity (cut entitlements, medicare and military spending?)

Default (why default when you can print?)

Print/inflate (the only politically feasible way to manage the debt).

Why not jack up rates like the 1970s?

It is a option at 30% debt to GDP (1970s), not at 130% debt to GDP (today).

We are facing the 1940s play book in which debt to GDP peaked at 119% before being inflated all the way down to 30% over 30 years.

Ray Dalio illustrates this well with the below chart.

Inflation will run hot until the debt is back under control, and a lot of the "pretend" has been removed from the economy through hard times.

Let me run you through what I mean by "pretend."

Pretend Jobs

Pretend jobs that are killing the productivity of Western companies.

Let me explain via meme…

Another way of putting this is China graduated 1.7m engineering graduates last year.

How many gender studies graduates did China (or the rest of the developing world) graduate last year?

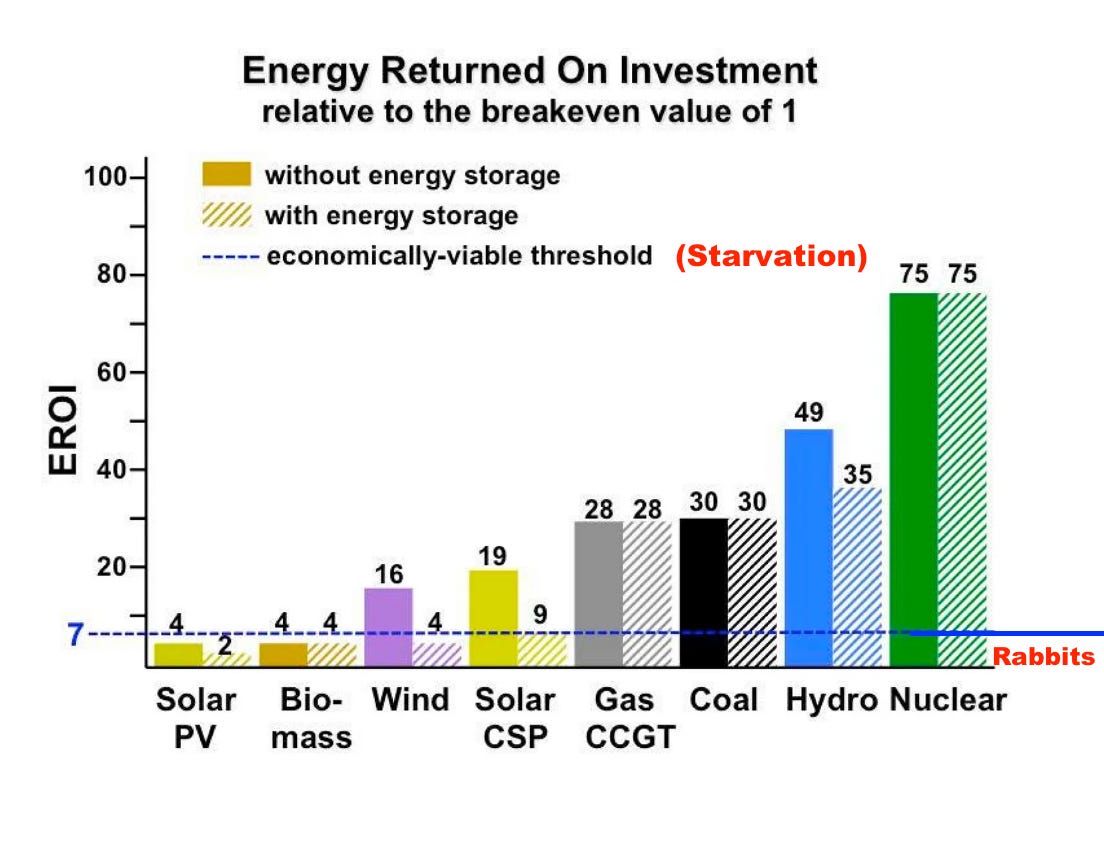

Pretending low energy density can replace high energy density.

I’ll borrow this from my piece The EROI Reduction Act

Consider the economy as a cheetah that has got fat-eating wildebeest.

Well, now this coalition of cheetahs has decided only to eat rabbits moving forward as it's more environmentally friendly (they breed quicker, and rabbit farts produce less emissions).

The problem is hunting rabbits has a low energy return on investment (let's call it an EROI of 4) in that it barely covers the energy needed to hunt them, let alone feed the cubs.

As efficient as the cheetahs get at hunting rabbits, they keep losing weight and will eventually need to return to high EROI wilderbeast or face starvation (there is actually rabbit starvation where you can die due to the lack of fat, i.e. storage.. I know I'm really pushing this analogy).

Losing weight in an economic sense means losing activities that rely on a large energy surplus (gender studies, diversity training, ESG consultants are the first to go).

This occurs as an ever larger proportion of the economy needs to be devoted to extracting and processing energy.

Pretending there isn’t a price to pay for fiscal largesse

Remember modern monetary theory?

There is a price to pay for increasing the US monetary base 7x since 2009, nearly doubling it from COVID.

The Inflation Reduction Act will do achieve exactly the opposite of what it intended (hows the Affordable Healthcare Act “Obamacare” working out?)

Lastly, pretending countries will keep buying treasuries at the scale the US requires, especially following the confiscation of Russia's reserves (you better believe China and Saudi Arabia took note).

The low inflation, easy money paradigm is behind us, and the question becomes where to best position for a high inflation, tight money, resource-constrained environment.

Whether you use the 1930s and 1940s or the 1970s history shows inflation comes in waves and this episode won’t be any different.

Pretending passive indexing is efficient capital allocation

It always seemed wrong to me that passive flows benefited the mega-caps, which didn’t need the capital (think Apple and Microsoft), while starving the small companies, which did. In what has become a recurring theme, a piece from Louis Gave explained it perfectly for me (he also touched on it in our recent interview).

Indexation is a form of socialism in action

We have also argued that indexing is the new in-vogue form of socialism. Capital is not allocated according to its marginal return—the foundation on which capitalism rests. Instead, capital is allocated according to the size of companies. Just as in the days of the old Soviet Union or Maoist China, the bigger you are, the more capital you get. It is hard to think of a stupider way to allocate one of the key resources on which future growth relies.

What’s this got to do with Moats and Cannibals?

In a low-inflation, easy money paradigm, the game was hunting out future growth; in a high-inflation, tight money paradigm, the game will become keeping up with inflation.

The hunt will be on for scarce assets producing real cash flow, those with the highest replacement cost having the largest moat.

It’s a law of capitalism that if a business achieves superior rates of return, other businesses will come after that opportunity, which will result in reduced rates of return. A business can’t just go around earning outstanding ROIC without competitors trying to copy them and compete with them.

The assets that are the hardest to replace and valued the cheapest are those where there is a wide spread belief they will be in terminal decline.

Highly cyclical sectors that have experienced sector wide bankruptcies has been my favourite hunting ground.

It's important to note most of these investments make sense regardless of the macro narrative I'm painting. It's challenging to end up in a value trap with company buying back shares at 2-3x free cash flow, or a restructured company with assets on the balance sheet for a fraction of their purchase price and rising demand for them.

The harder it is to replace an asset, the larger the moat. The moat is a function of money, speciality labour, resources, and energy.

The game becomes picturing yourself five years in the future and what will investors be climbing over each to buy to protect themselves from inflation while there is little ability to increase supply.

Infrastructure companies such as Enterprise Products Partners LP or Enbridge Inc are difficult, if near impossible, to compete with their distribution/pipelines; this is well understood so it's difficult to get them dirt cheap.

Royalty companies have the same issue in that everyone is aware of the quality of the business model so the valuation reflects it.

My preferred assets are those which are cyclical yet the market is convinced the cyclicality is over as the demand for them is in decline.

Examples:

Drillships

Semisubmersibles

Jackups

OSVs

VLCCs

Product Tankers

Coal mines

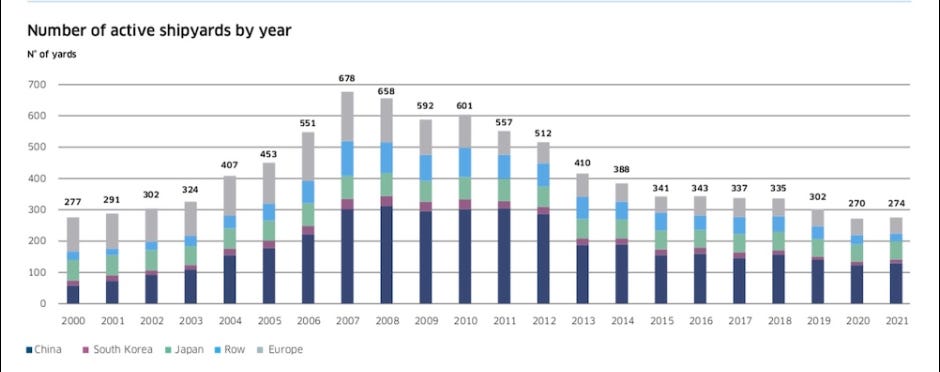

All these, except the coal mines will be fighting over the same limited shipyard capacity (down 60% from the peak) which is already booked out to late 2027 with mainly container ships and LNG carriers..

This gives a four years plus build time minimum that these assets could print cash before they could do what cyclical companies alway do and over order setting the stage for oversupply.

A lot of these themes overlap. VLCCs, Capsize, OSVs drillsips can't all hit the wall and be over ordered in a five year period either (being at the back of the queue could mean outstanding returns).

What does this have to do with Cannibals?

I borrowed this idea from Mohnish Pabrai's Presentation and Q&A at Boston College and Harvard Business School

The two big takeaways from this presentation were:

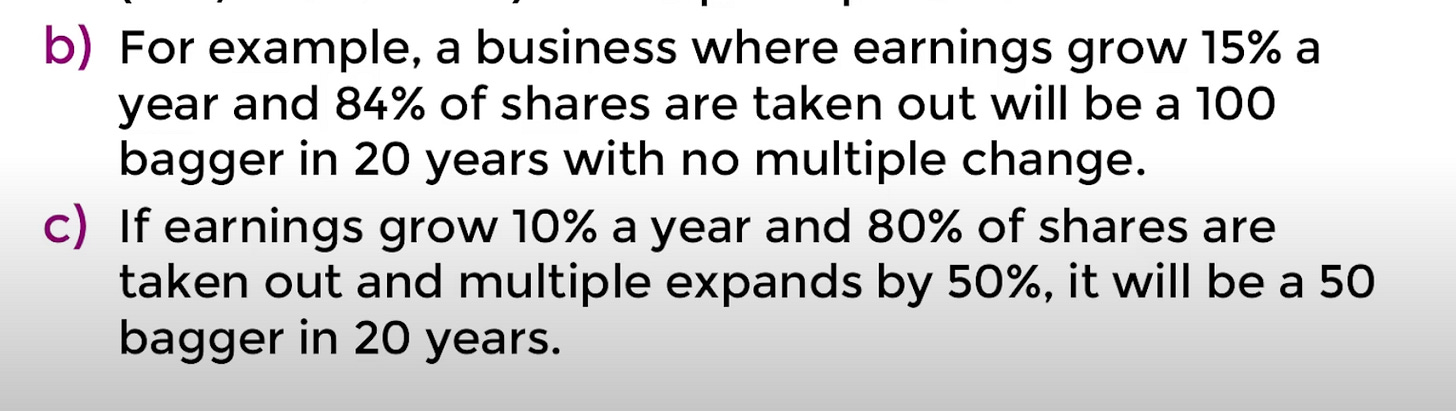

You can massively benefit with or without multiple expansion. If the market never re-rates a company it can re-rate itself by aggressively buying back its cheap stock.

The second is how extreme the returns can be as the corner above 80% of the float (no small feat!

Yes this strategy takes years to really show up which is what I believe we have up our sleeve with many of the assets mentioned earlier.

It'll probably take a few years for investors to grasp what's happening and achieve some form of Mag7 status, maybe Moat7….

We can already spot the green shoots of this strategy in many companies which I'll run through my prime candidates.