There is always a trade-off when hunting out truly hated asymmetric setups.

I’m guilty of romanticising catching the below chart just before it breaks out.

To list a few flaws in hanging out in these types of setups:

Dilution

Bankruptcy/re-capitalisation.

Time/opportunity cost

Being early can be painful.

For a case study in opportunity cost, look no further than uranium. If you had spotted uranium bottoming at the end of 2016, you would have had little to show for it until the end of December 2020 (I used market cap as stock price doesn’t reflect dilution).

Plus, these were companies that worked out.

I could throw in Goviex to illustrate the downside of miners (having lost their Niger project, they have rebranded a Zambia developer).

Or Paladin as an example of bankruptcy.

“When” do these ships get replaced?

I've always loved Rick Rules observation that an investment thesis should start with "when" not "if"(I’ve always thought battery metals was a “if” question, in “if” this battery chemistry is the ultimate winner).

I spilled enough digital ink on orderbooks in my last post so will avoid going over it again here. The bottom line is there is a whole lot of ships moving into scrapping age over the next 5-10years.

I like the chart below as it reminds us that "average" scrapping is exactly that, with some ships trading for decades past the “average” (back to the first point I made of time/opportunity cost in these setups).

Limited Capacity (for now)

Ship yard capacity has been decimated and is down around 60% from the peak. The proportion of the industry that survived is rapidly maxing out utilisation, as I went over in the last piece, with Containships and LNG carriers clogging up the shipyard capacity out to late 2027.

Granted, thinking there won't be a supply response to this could get you trouble, particularly with China, which already controls nearly half of global shipyard capacity.

New build prices out of China are important to monitor, as it's not much use working off higher replacement costs as the Chinese pull a BYD on your thesis.

Take this recent example with PSVs:

TradeWinds is told that the Greek tycoon’s Capital Offshore has ordered four firm platform supply vessels at Fujian Mawei Shipbuilding, with four options attached.

The deadweight tonnage of the diesel-electric ships is not known, nor have delivery dates been disclosed, but handover could potentially begin from 2026.

Brokers have estimated a new PSV as costing between $40m and $50m, with the Marinakis deal possibly towards the lower end of that range due to the size of the order.

Adding shipyard capacity is one thing, but keep new build costs down is another especially with input costs continuing to rise (Newbuild prices approach 2008 record levels)

In June 2022, there were 153 active shipyards, according to Greece’s Xclusiv Shipbrokers. This number climbed to 180 this month, with China accounting for most of the growth.

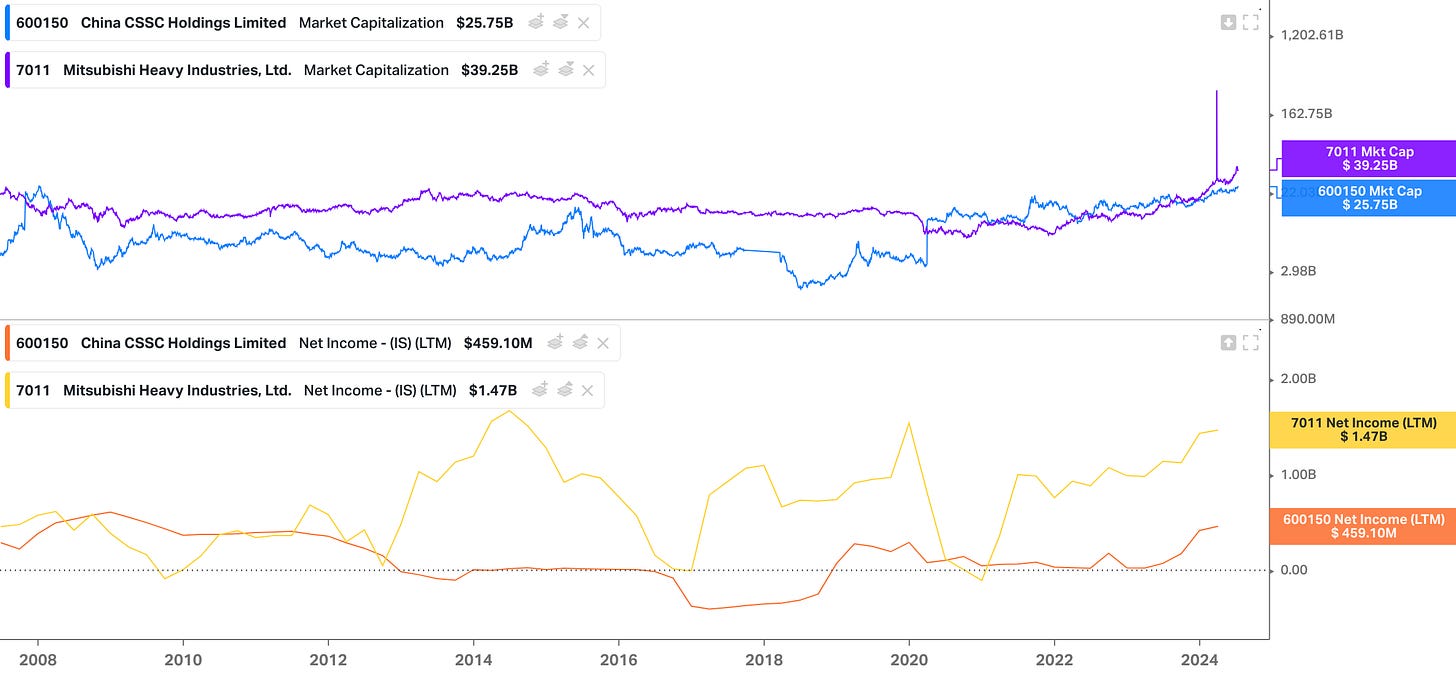

I'm not digging into the major shipyards as the asymmetry isn't there for me (these are the 60% that didn't go out of business). These are strategic industries with defense and employment implications, meaning they are often heavily supported by respective governments and are not as cyclical as you'd expect.

Take the market caps and net income of two of the biggest in China CSSC Holdings Limited and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

How I’m playing this sector?

My angle is to find shipyards specialising in offshore which have either recapped or gone bankrupt and relisted (in the case of the new position, it has now been bankrupt twice) and, ideally have a vessel chartering/fleet side of the business to produce cashflow until the offshore shipyard business turns around.