It’s not hard to identify the various facades in the West. The tricky part is knowing when it will matter, since in a financialised system, there can be endless fuckery until you actually hit a real constraint (something that further printing/financialisation can’t fix).

As you’ve probably guessed from the title, I’m seeing events in the futures markets that can’t be “papered over”.

Every now and then, I read a piece that helps me connect the dots. This was one such piece: The Return of Matter: Western Democracies’ material impairment

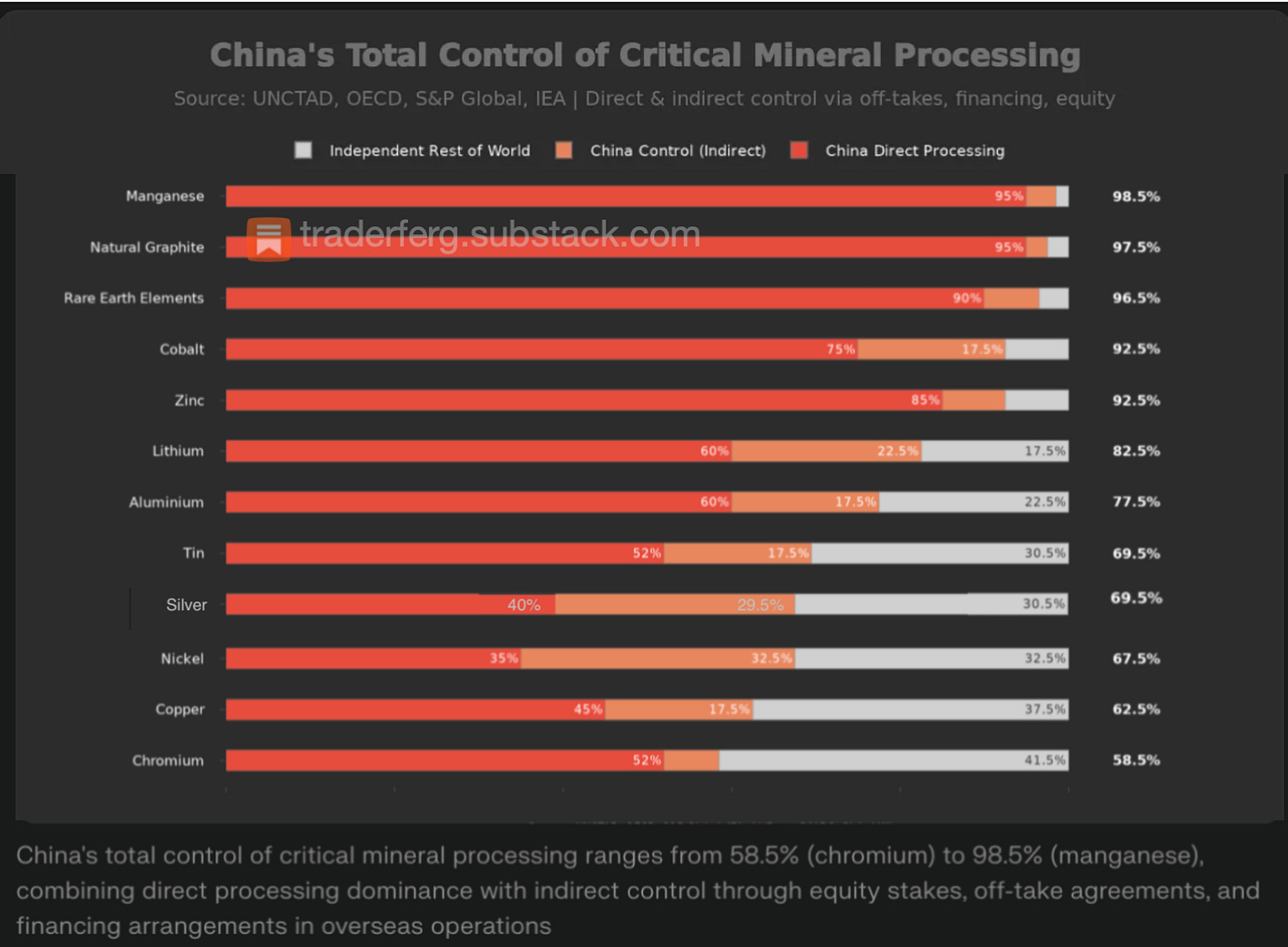

While most are aware that China dominates global refining/processing, the extent of it when you factor in indirect control via financing and off-takes is pretty shocking.

Since 2000, Chinese policy banks have channelled heavily subsidised credit into overseas projects, with roughly 83% of mining finance in developing countries flowing to operations where Chinese firms already hold equity, effectively locking in long-term off-take.

I mashed together processing and financing datasets in Perplexity (so take it with a pinch of salt) and came up with the chart below, which illustrates the extent of Chinese control over processing.

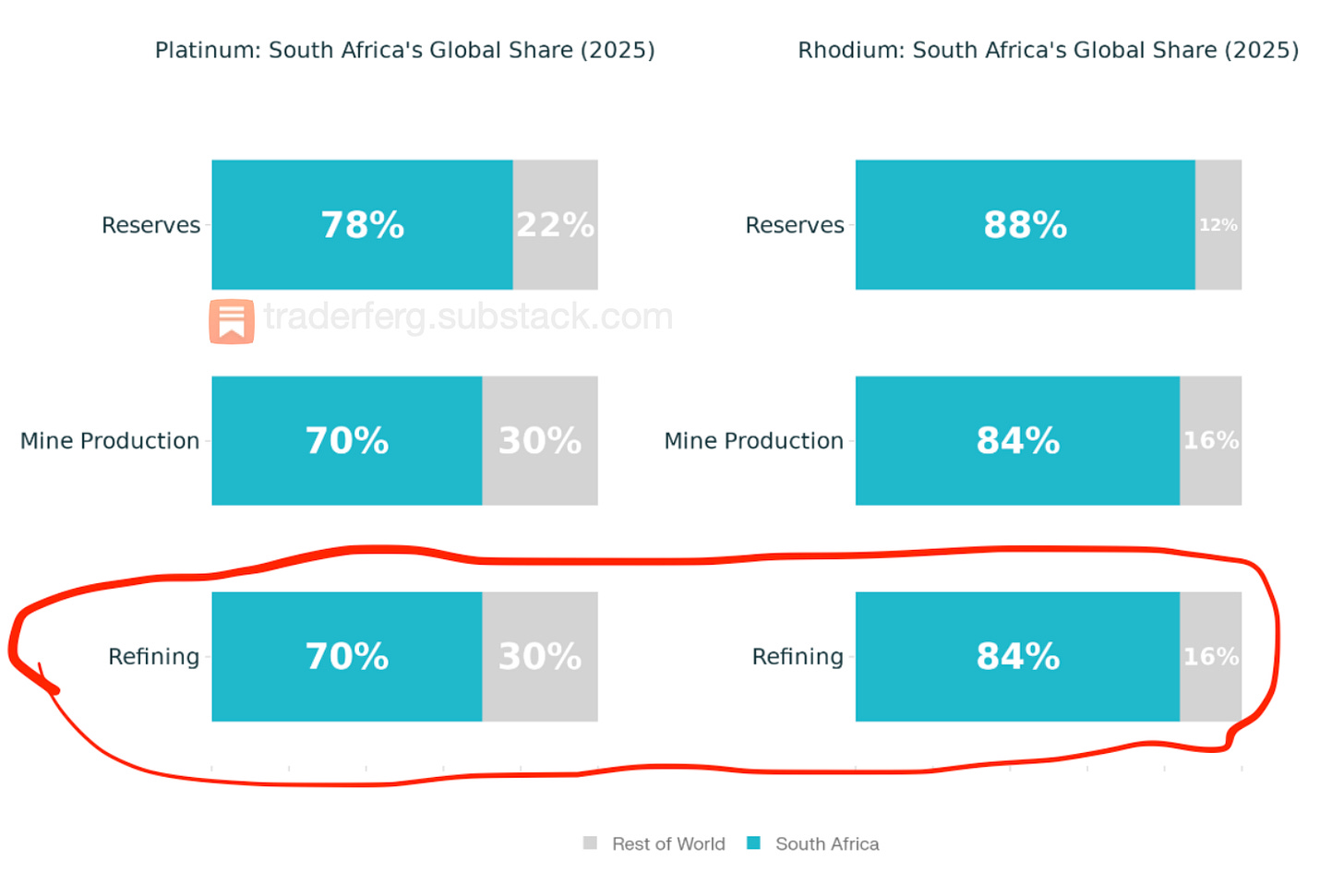

One mineral (labeled critical by the Chinese) that is absent from this chart and for which they don’t control any processing at all is platinum.

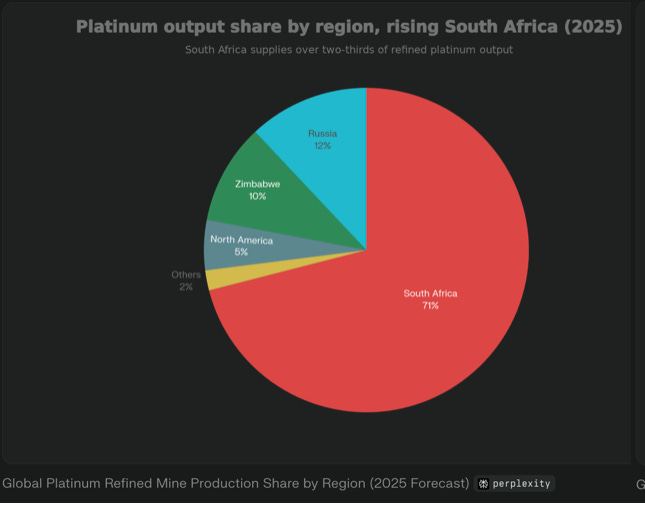

This is where the jigsaw pieces came together for me: South African PGM producers, who represent one of the largest vertically integrated mining and processing operations globally and remain substantially outside Chinese control through ownership, financing, or off-take agreements.

For comparison, Rio Tinto, BHP, and Freeport-McMoRan collectively control approximately 5.1% of global refined copper production through their fully integrated operations spanning mining through smelting and refining.

Between South Africa and Zimbabwe, you are looking at 81% of global platinum refining (84% for rhodium).

Also, while Impala/Zimplats has a significant smelting operation in Zimbabwe, it still relies on its South African operation for final separation.

Impala Triples Platinum Smelting in Zimbabwe With New Plant

Despite this expansion, Zimplats does not refine precious metals to their final separated form. The facility produces converter matte (an intermediate containing mixed PGMs and base metals), which is then shipped to Impala Refining Services (IRS) at Springs, South Africa, for final separation into pure platinum, palladium, rhodium, and other PGMs.

China has cornered refining of South African commodities like chrome (SA = 46% global production) and manganese (SA = 37% global production), the ore is relatively high grade, i.e., ~40%, which makes it economic to ship millions of tonnes of raw rock to China.

This doesn’t work with PGM ore as it is ultra-low grade and measured in grams per tonne. This means you cannot ship the raw ore to China since it would mean shipping 99.9% waste rock.

The economics, combined with the BEE (Black Economic Empowerment) hurdles, meant the Chinese never got any control over South African PGM refining.

Chinese interests (Zijin Mining & Jinchuan Group) do control 2-4% SA PGMs on an operational basis (4-5% once all committed projects reach full capacity). Although this is mostly processed by South African refiners.

The South African PGM refining sector remains highly consolidated among four major operators:

Anglo American Platinum (Amplats): 40-45% market share.It operates three smelters (Polokwane, Mortimer, Waterval) and two refineries (Precious Metals Refinery, Base Metals Refinery)

Impala Platinum (Implats): 30-35% market share (Springs refinery with IRS operations)

Sibanye-Stillwater: 15-20% market share (Marikana operations with integrated smelting and refining)

Northam Platinum: 10-15% market share (Zondereinde smelter with external refining partners)

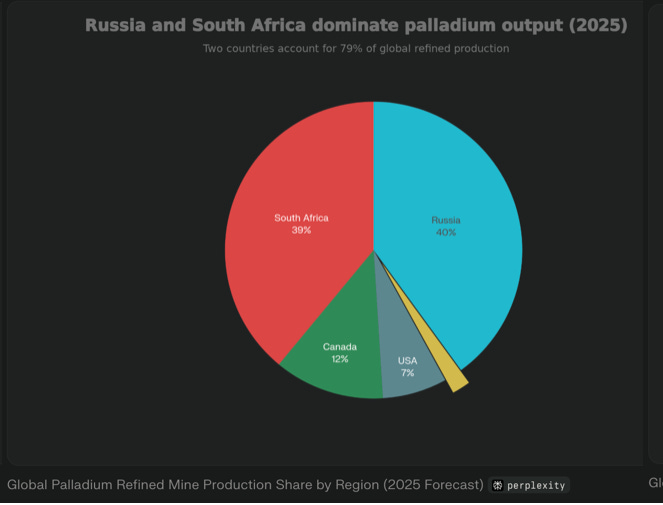

What about Palladium?

Geopolitically, palladium isn’t a concern for China as it’s in bed with Russia; platinum is the significant risk, with its extreme concentration and vertically integrated SA miners.

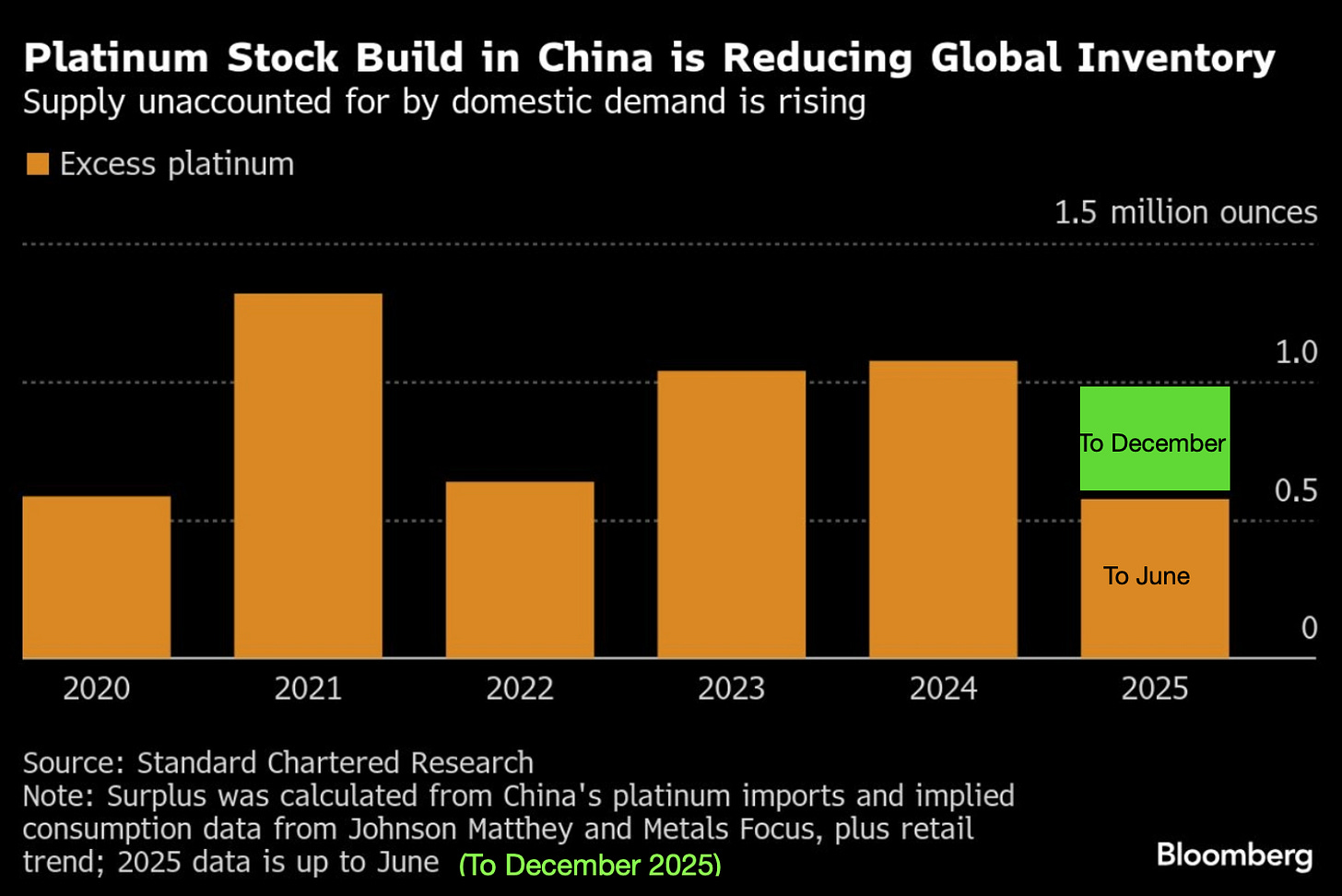

The Chinese have aggressively stockpiled platinum because they couldn’t gain sufficient control over the supply chain of a critical mineral.

Platinum Shadow Stockpile

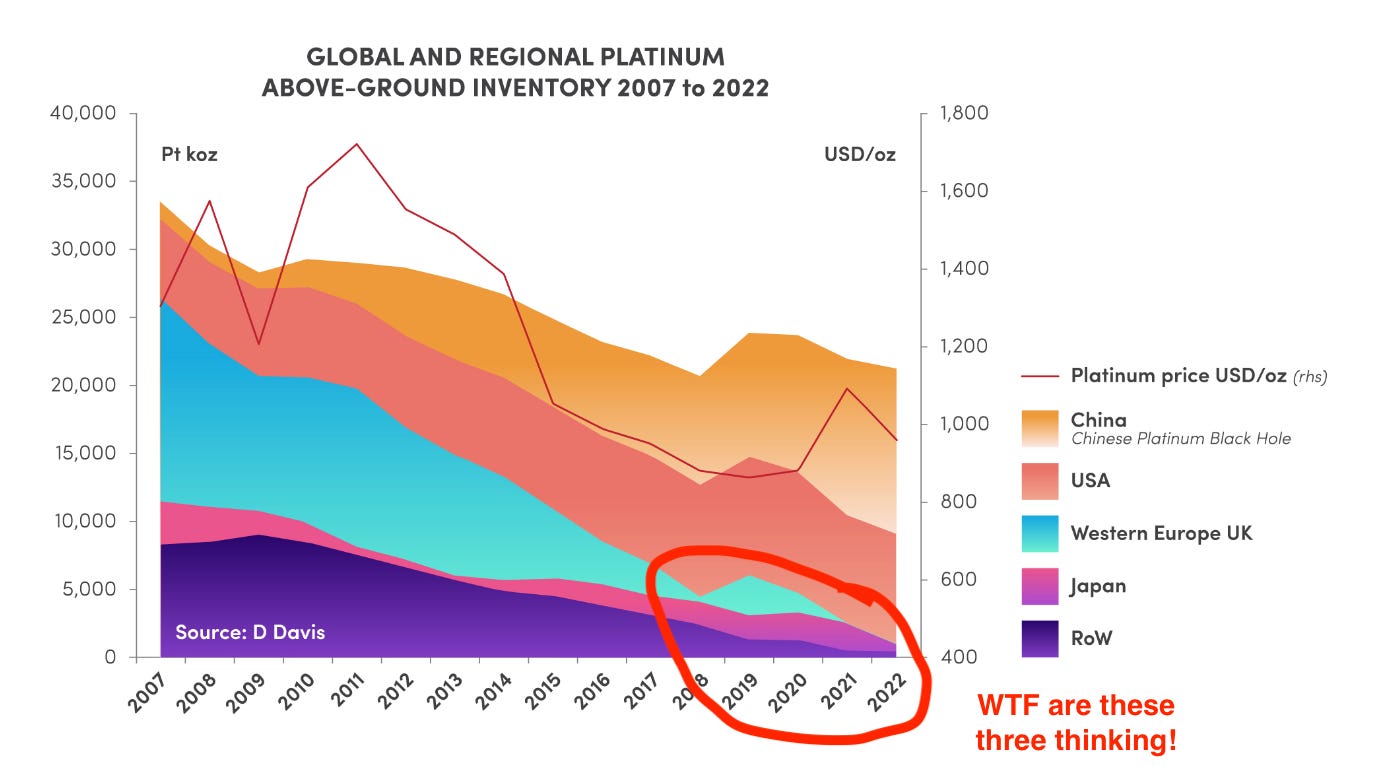

While it’s all guesswork about where China’s above-ground inventories stand today (China isn’t going to disclose them), Chinese imports have ramped substantially since Dr David Davis published his 2023 report and have hit a record in recent months.

My calculations indicate that by 2022 China’s AGI had grown to around ~12moz, which represents ~57% of the apparent global platinum AGI of 21.2moz.

While the WPIC had China at 80% of AGI in mid-2023!

The World Platinum Investment Council (WPIC) estimates that more than 80% of all global above-ground platinum stocks are now concentrated in China

- WPIC How to solve an almost 1 Moz platinum market deficit (May 2023)

Tracking Chinese platinum imports in excess of demand has them stacking a further ~3million ounces on top of Dr Davis’ ~12 million ounce estimate in 2022. This brings their holdings to ~15moz (~83% global AGI) against WPIC-tracked platinum AGI, which stands at 2.978 moz (~17% global AGI) total above-ground inventory tracked by the WPIC, which includes all vaulted platinum holdings globally—excluding ETFs, exchange stocks (like CME), and working inventories of producers/fabricators/end-users.

Side note: The U.S. largely sold off its strategic platinum reserves decades ago. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the government determined that platinum was sufficiently available from diverse global sources and no longer required a massive strategic reserve for defense purposes.

The One-Way Valve into China

Both the SHFE silver futures contracts and, more recently, GFEX Platinum & Palladium contracts have distinct purity specifications, creating two markets.

Touching on silver first:

COMEX silver requires a minimum fineness of 99.9%

SHFE silver requires 99.99% fineness

That 0.09% matters as SHFE silver cannot freely substitute for COMEX-grade silver (99.9%). The two markets cannot serve as pressure-relief valves for each other.

Chinese industrial demand pulls physical silver out of London and COMEX vaults into SHFE delivery. SHFE is experiencing severe backwardation, yet COMEX paper markets continue to “operate nominally”. Behind the scenes is a different story: In the first four trading days of December 2025, more than 60% of COMEX's registered silver inventory (47.6 million ounces) was claimed for delivery—an unprecedented drain in less than a week.

This obviously benefits Chinese domestic producers and manufacturers: they can export lower-purity silver to COMEX markets when needed, but ensure that SHFE deliveries represent 99.99% silver locked within China’s industrial ecosystem.

The paper market has become hostage to the physical market, as purity specifications create two distinct markets rather than a continuous one.

China also controls ~70% of silver processing (40% directly and a further 30% indirectly), so it is in a far stronger position than with platinum (Chris Tindale touches on this in The Return of Matter).

The Derivative Mineral Trap: Silver as a Host-Metal Prisoner

Silver’s vulnerability is compounded by a geological reality that Western planners frequently overlook: it is a host-metal prisoner. Unlike iron or copper, which are mined for their own sake, approximately 70% of global silver supply is produced as a byproduct of lead, zinc, copper, and gold mining. Primary silver mines are rare. Consequently, the global supply of silver is inelastic; it is constrained by the mine plans and cap-ex cycles of these base metals, not by the price signal of silver itself. If the price of silver doubles but copper demand softens, copper miners will not ramp up production just to harvest the “hitchhiker” silver, leaving the market in structural deficit regardless of price action.

Crucially, the control of these derivative flows is determined not by where the ore is mined, but by the geographic location of the smelter. When copper or zinc concentrates are refined, silver is captured in the anode slimes and residues—the “waste” streams of the refining process. It is only at this midstream stage that the silver is separated and purified.

Sponge Delivery: A World First

The key point of the new GFEX platinum and palladium contracts is that they allow ingot or sponge delivery, a world first (they began trading on November 28, 2025).

COMEX Platinum & Palladium require 99.95% Ingot

GFEX Platinum 99.9% Sponge or Ingot

GFEX Palladium 99.95% Sponge or Ingot

The GFEX platinum sponge contract specifies a minimum fineness exceeding 99.9%, which is notably lower than COMEX’s 99.95% standard.

So it’s the opposite of SHFE silver’s higher purity requirement (solar and semis). A 0.05% lower purity reflects the different industrial requirements of Chinese automotive catalyst manufacturers, who typically work with sponge form material and may tolerate slightly lower purity.

It’s a significant advantage for Chinese domestic users, who can take physical delivery of sponge directly without conversion costs (COMEX delivery of ingots requires melting and refining).

Regardless of the reasoning, it’s the same point I made with silver in: “The paper market has become hostage to the physical market due to the purity specification creating two distinct markets rather than one continuous market.”

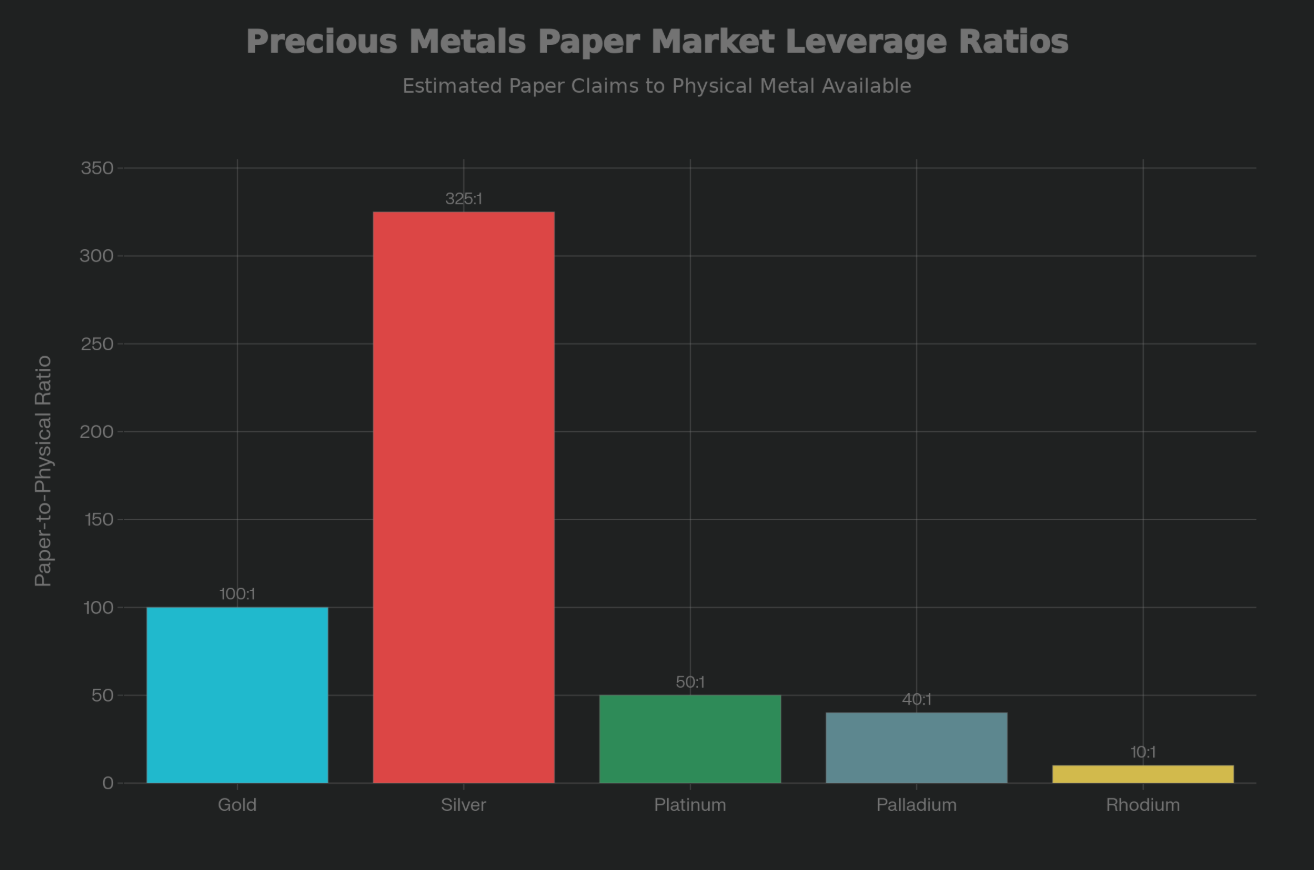

Setting Fire to Paper Markets

China has long complained that Western markets suppress commodity prices via “paper shorts” (unbacked derivatives). By holding the physical inventory and offering a deliverable futures contract, China can discipline the paper market to align with its physical reality.

You could potentially even see two prices emerge: a “China Sponge Price” (lower, stable, China making its strategic stockpile available internally on GFEX) and a “World Price” (scarcity-driven on COMEX).

The rest of the world’s industrial users are highly vulnerable to a supply squeeze, as they hold only ~2.16 million ounces (roughly 6 weeks of demand cover), which industrial and investment demand will have to fight over.

Western automotive companies cannot currently access physical platinum via GFEX platinum contracts for delivery. The Guangzhou Futures Exchange platinum and palladium contracts launched on November 27, 2025, are presently restricted to domestic Chinese participants only.

QFI Access Limitations; While China has been expanding its Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFI) program to allow foreign access to various commodity futures, platinum and palladium contracts are notably absent from the QFI-eligible products list

Western banks and industrials are now naked short against a physical supply locked in China.

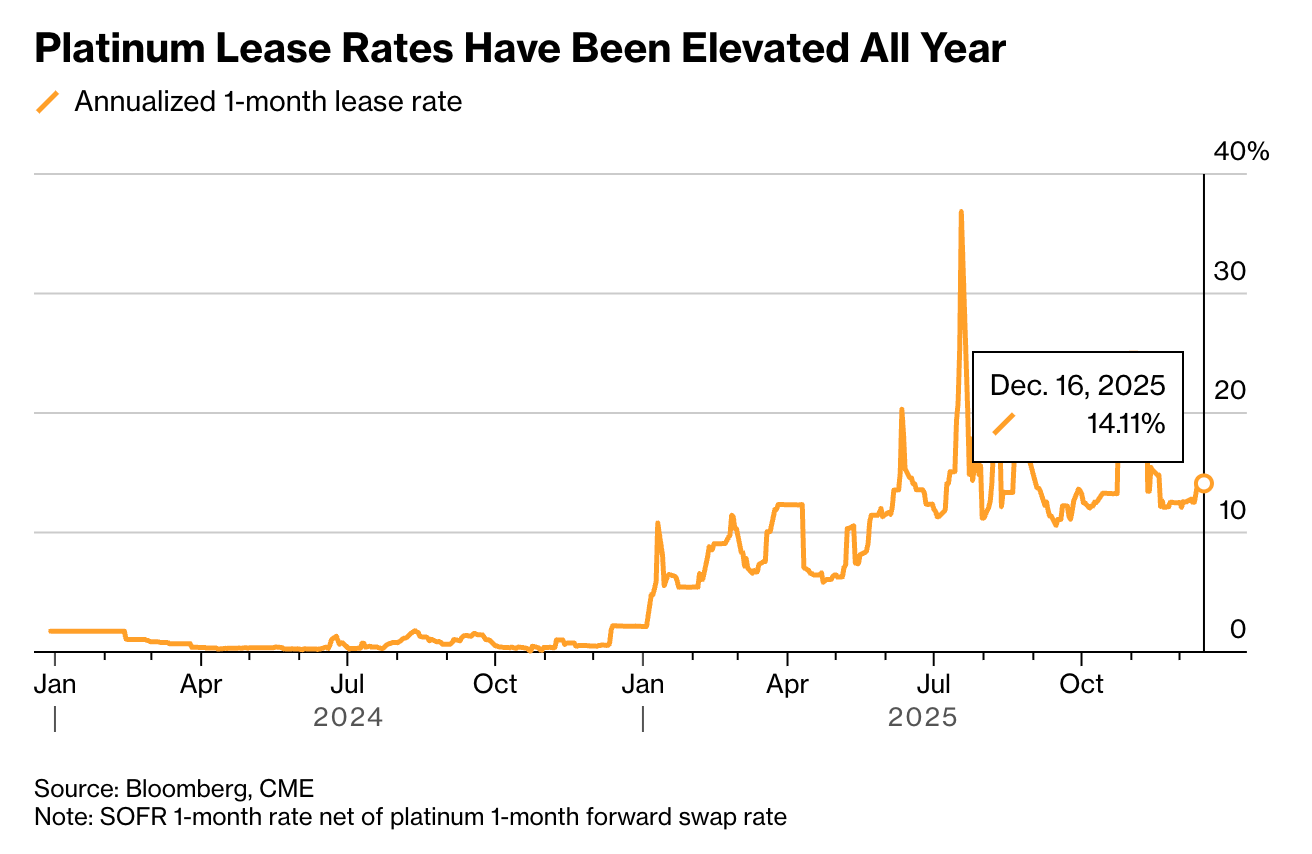

This is why the platinum lease rates are telling investors, as they force immediate hand-to-mouth buyers to access the spot market at any cost.