Having a heavy filter on ideas is key in the investment game, as there is no shame in missing something that takes off.

Every day, there will be some company or asset experiencing a bull market, and it's no loss that you’re not involved.

My quick filter has always been to identify hurdle rates, which are investments within my circle of competence that I view as sitters for a 2-3x return given a long enough timeframe.

I put together a video on this idea back in my Crux days, outlining how I used hurdle rates in my portfolio. At the time (October 2020), my hurdle was physical uranium at $30/lb (YCA or U.u), and I was switching to Whitehaven Coal, which was $2.80 share at the time.

The reasoning is pretty simple;

First, is it in my circle of competence?

So many investors assume complicated implies sophisticated when simplicity is the true form of sophistication when it comes to investment success.

-Ben Carlson

For example I get sent resource plays all the time and pass on 97%.

“It depends on permeability and post frac flow rates” I’m out..

“Mine has x grade in x mineralisation based this sample” I’m out*

*Yes, I own miners, but they are mostly cashflowing or restarts; the only exception is uranium, where I have enough conviction in the macro set-up to own early developers and even a shitco/moose pasture collector.

Opportunity > Hurdle rate

Second, is there a high likelihood of a better risk-reward than my hurdle rates? If not, why am I wasting my time even considering this opportunity?

The maturation of every investor starts with absorbing almost everything and ends with filtering almost everything.

-Ian Cassel

With that out the way, I'm seeing a lot of interesting opportunities right now.

I'll start with tin because I understand it best, having dug into it previously (February 2021 and June 2022).

To start tin is a tiny market.

The visualisation below illustrates it well, with tin representing 1.5% the size (tonnes) of copper (2021) or 4.5% of copper's market value (using today's prices).

Solder accounts for nearly half of tin demand, which is why it is often referred to as "metal glue." It's quite resistant to substitution since most devices only require a few cents of tin. Most substitution efforts have involved removing lead from solder with mixes such as copper-tin and silver-tin mixes.

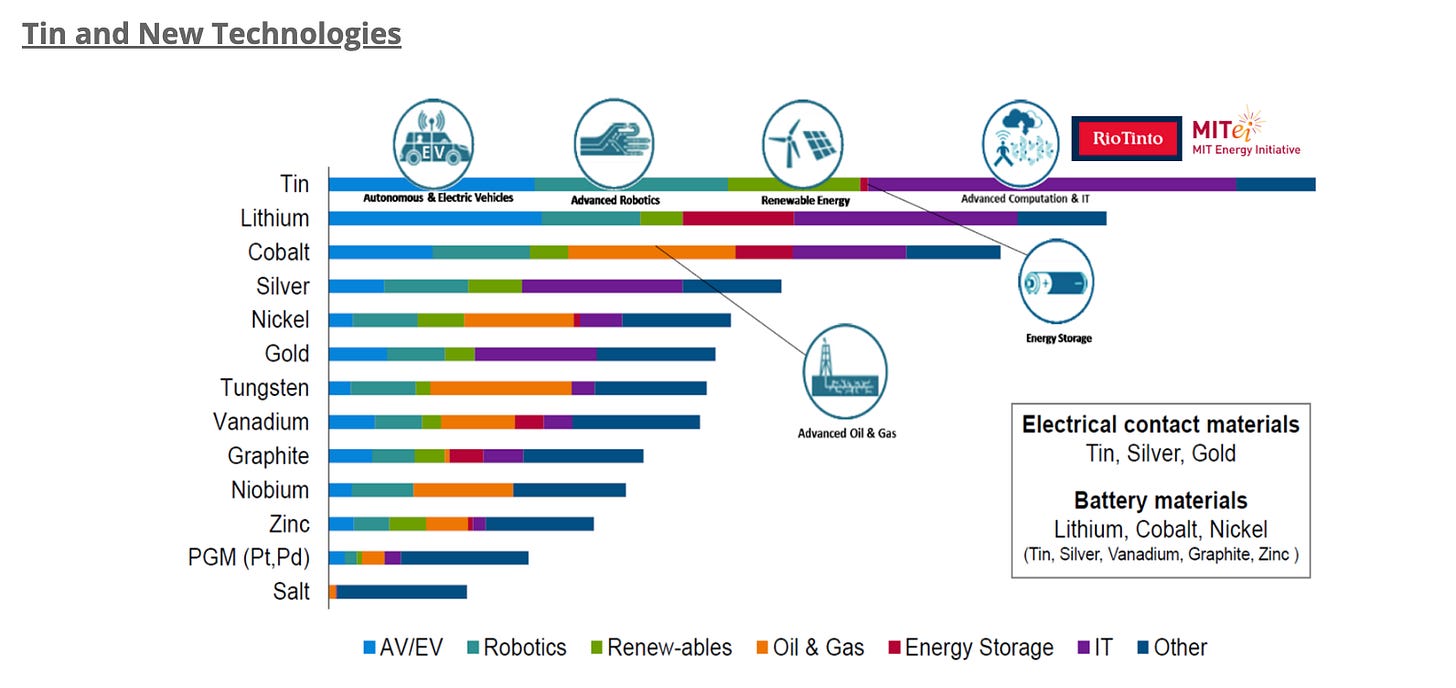

I remain highly suspicious of demand projections for renewables and EVs. Yet, tin is unique in that it stands to benefit the most from this demand in conjunction with growth in semiconductor demand. At the same time, little to nothing is being done about it on the supply side, unlike other "transition metals", such as lithium and nickel, which have majors throwing their CAPEX at them.

One big lesson I learned since first pitching tin in February 2021 and buying more in June 2022 was to keep an eye on semiconductor sales as a proxy for tin demand. The trade worked great during the 50% ramp during COVID, when everyone was stuck at home and required laptops/tablets for work and schooling. That demand rolled over -20%, and I dumped tin in favour of rolling the capital into more offshore oil services.

Well, as you can see, semiconductor sales are ramping again.

In short, I think tin demand should hold up from here as there aren't any crazy expectations built it's future demand, and its demand is quite broad-based and tough to substitute, unlike, say, lithium.

Supply

Tin supply is where the thesis gets interesting, as it has one of the lowest reserve-to-production ratios I've seen. Going back to 2011, tins' reserve-to-production ratio was the lowest of all the metals, while production was growing steadily due to the use of computer chips in everything.

In a outcome not to dissimilar to US shale, Myanmar burst on the scene in 2013 with large easy to access tin resources.

The story is classic high grading (Myanmar tin production may have reached peak Aug 2016)

In 2014 most production came from several large open pit mines, but these have been largely depleted and today most mining is underground, with higher operating costs and lower ore grades.

• While grades of more than 10% were common two years ago, most ore mined now grades between 2 – 3% tin. A big newly discovered high-grade (7-8% tin) resource was exploited through the second half of last year and the early part of this year, but this is now largely depleted.

• Until recently ore grading less than 3% tin was stockpiled as mine owners sought to make a quick return from the higher grade material. However improvements in processing capacity and technology, and a rising tin price, have now made it economic to treat this stockpile.

Since this article was posted Myanmars exports to China have been on the decline.

More recently, mining ceased altogether with the Wa State suspending it.

Myanmar's Wa State Army keeps global tin market guessing (January 11th 2024)

The Wa State, the largest of the country's ethnic groups, ordered the suspension of all mining and processing operations in the autonomous region at the start of August for an extensive audit.

That ban has been lifted with effect from Jan. 4 for most mining. The major exception is the Man Maw mine, which accounts for almost all tin production in a region that is the world's third largest producer and the dominant supplier to China's smelters.

China was wise to this, with it having stockpiled tin since 2022.

Still stockpile or not where is the future tin supply going to come from?

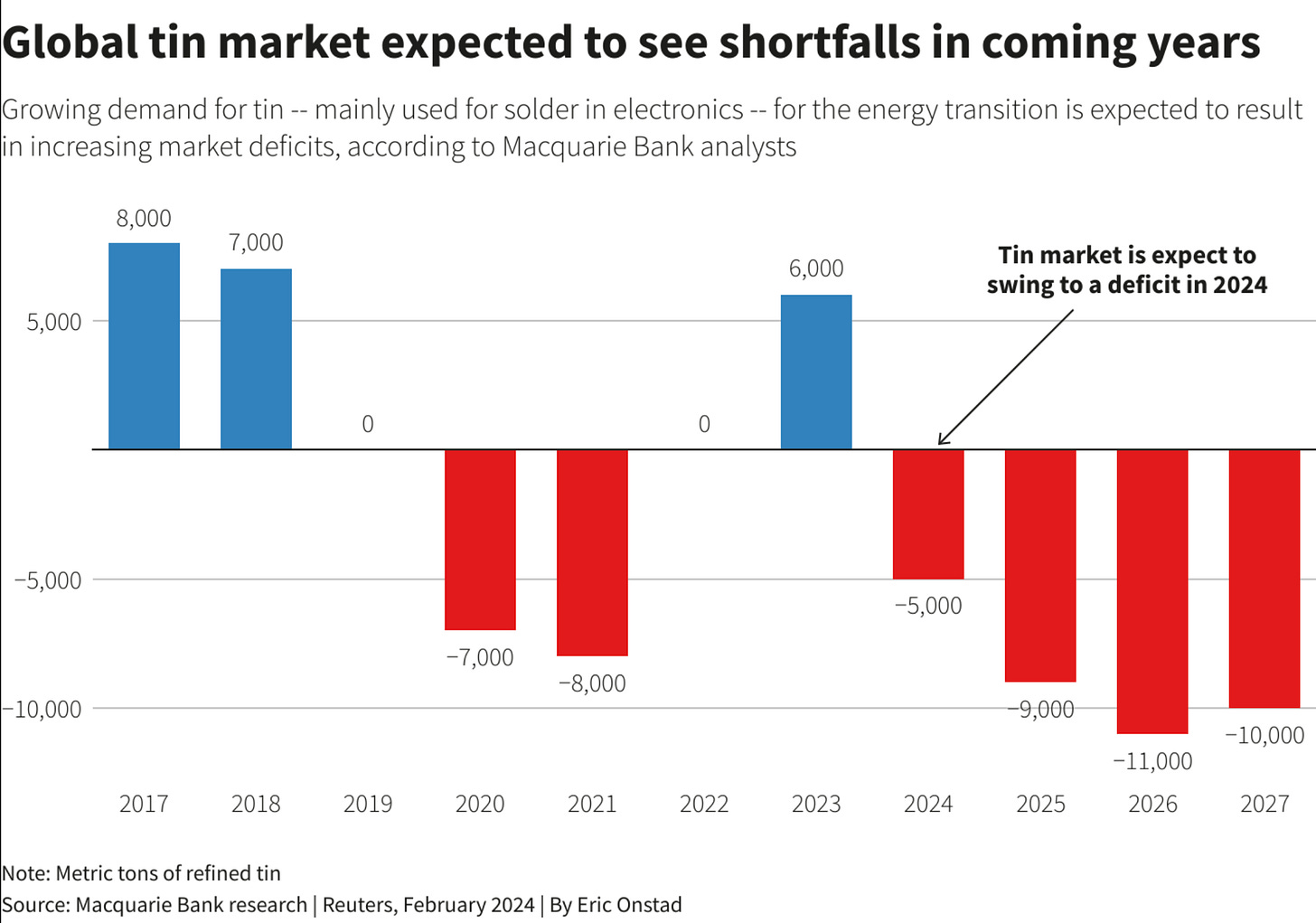

I love a commodity story with solid demand, a big deficit and no clear path to balancing it.

Indonesia would be a prime candiate to replace Myanmar tin exports to China, except Indonesia is focused on its “downstream policy.” Which will be quite disruptive as the ability to process/add value has to be built out.

“If other economies wish to get their hands on the said commodities, they can either import the processed goods from Indonesia or build a plant in the country.”

Everything Must Go According to Plan: Jokowi on Export Restrictions

Column: Tin supply trapped in resource nationalism squeeze

In preparation for the downstream policy the Government is cracking down on the sector to clean up illegal mining and corruption.

Growing concern over Indonesian output amid licensing delays

Indonesia’s tin industry has recently come under increased government scrutiny, with police investigations being launched into the sector in late-2023. This comes as part of a broader push to ensure compliance with mining, trading, and export regulations and to safeguard the country’s critical mineral resources. The initiative follows similar interventions in the nickel industry last year.

Indonesia was responsible for 18% of global tin production in 2023, and this is the numbers so far this year!

Refined tin exports in January stood at 0.4 tonnes (99% decrease year-on-year), while exports edged higher to 55 tonnes (98% decrease year-on-year) in February.

Zooming back out

Between Myanmar, China, and Indonesia, you've got 60% of the global supply with around 15 years of reserves left, and as mentioned earlier, with Myanmar, the difficulty/cost of extracting those reserves climbs as the easy stuff is mined first (same goes for majority of reserves nearing the end of their life).

It doesn't seem to be a stretch to expect further disruptions from Myanmar and Indonesia over the coming months/years, representing 37% of supply. Meanwhile, once China works through its stockpile of tin, it will be facing 5-10k tonne deficits in the market from 2024-2025.

There is nothing in the pipeline to correct this deficit either.

Recycling?

Recycling needs to be considered, as it contributes to around 31% of tin consumption currently. The recycling input rate for tin has varied between 30-35% over the last decade, with price being the main driver. Granted, this doesn't seem to be playing out, considering the tin price tripled in 2022, yet RIR actually fell:

If I had to guess I'd say this is due to the tiny amounts of tin in most electronics making it uneconomic to recycle it even with a substantial move like we saw in 2022.

Summary

So, in summary, I am not sure where the green (probable mine supply) is going to come from; secondary supply via recycling isn't very responsive to price, and primary supply is in decline. Meanwhile, refined consumption growth looks pretty robust to me.