There is a stark contrast in whats happened the past five years between China and the West. While the media had everyone focused on the Chinese real estate bust, few picked up on the fact loans to the Chinese industrial sector had ramped to a similar level to those at the peak of the real estate boom.

China encouraged cut-throat competition across industries the CCP deemed essential (Made in China 2025). EVs are the cleanest example, peaking at around 487 EV manufacturers to today where there are 70 still existing when really it's eight companies, and in winner-takes-all fashion, BYD has 36.1% domestic market share as of Oct 2024.

In Western countries, they cut the throat of competition via monopolies, oligopolies, and cartels, with extensive formal government regulation, regulatory capture, and price fixing. The subsidies handed out were life support rather than to fuel competition in industry. We came up with terms like stakeholder capitalism, pretending ESG and DEI would add value.

Or to explain via meme:

The fourth thing never to fade

In my piece on getting long Chinese Tech, I went over Lyn Aldens, Three Things Never to Fade. If I were to add a fourth thing to this list, it would be the Chinese in CAPEX heavy industry.

I've followed this rule across the majority of the portfolio, with one glaring exception in shipbuilding. The Chinese are dominating shipbuilding and gaining market share at a rapid rate.

This begs the question of whether it is wise to have over 10% of my portfolio in Seatrium, Nam Cheong, and Marco Polo.

Chinese domination of the shipbuilding industry

The trend is clear, so is this a place to put capital to work?

The shipbuilding output gap has widened post-2020.

You'll often see millions of GT or CGT on shipbuilding graphs to differentiate the complexity of building certain ships.

M GT (Millions of Gross Tonnes) = Total internal volume of ships (no adjustment for ship type).

M CGT (Millions of Compensated Gross Tonnes) = Workload/complexity of shipbuilding (adjusted by complexity factor, 1M GT could be 0.5M–2M CGT, depending on economic/technical effort in construction).

A bit of history

Japan has been giving up market share for decades, having been the dominant player in the 1980s and 1990s. South Korea overtook Japan in 2000, while China overtook South Korea in 2010.

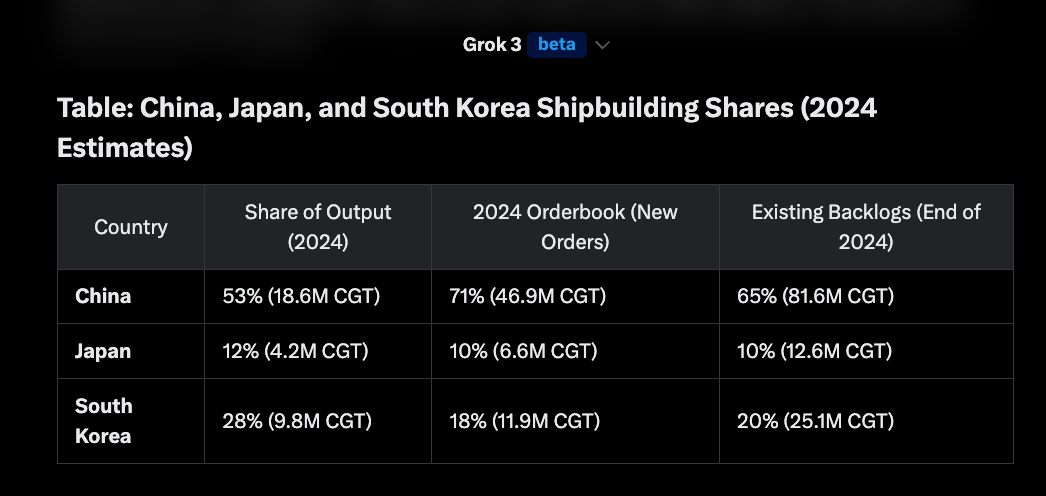

If you measure by orderbook, you can see in 2007 the three countries had a third each; fast forward to today, and China has two-thirds of the global orderbook.

While the global orderbook may be picking up, it’s still less than a quarter of its peak as a share of the fleet in 2008. It’s even more extreme when you consider containerships and LNG carriers make up two-thirds of that order book.

Shipping is highly cyclical for a reason: an oversupply of new builds in 2008-2010 resulted in over half the global shipyards going bust, reducing capacity. Yet that large proportion of ships built in that window are all going to hit recycling/scrapping age at the same time.

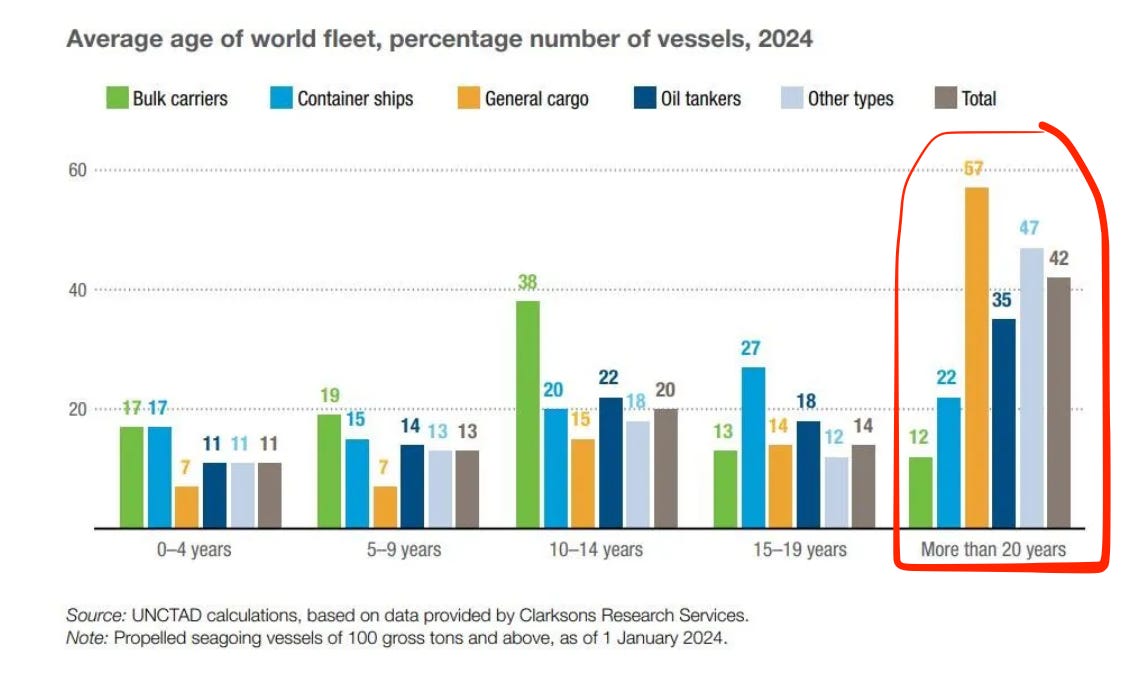

Take this chart, which illustrates the large percentage of the world fleet older than 20 years.

While 20 years is by no means a hard limit, following which they are scrapped, survival rates decline rapidly past the 20-year mark.

You can break shipbuilding down via output, latest additions to orderbook, and total orderbook/backlog.

Any way you cut it, China is eating Japan's and Korea's market share at an accelerated rate since 2018.

South Korea

While the South Koreans are losing marketshare on a total orderbook basis, they are dominating the LPG and LNG carrier market which make up approximately 60% of their orderbook.

Korean shipbuilders hold a dominant 93% share of the LPG carrier market, securing 33 out of 37 orders in the first half of 2024. They have also received orders for 44 LNG carriers from Qatar out of a total of 62 orders over the past two years. Meanwhile, China has experienced the strongest growth in exports of motor container ships over the last two years, a segment that is not the primary focus of Korean and Japanese shipbuilders.

This specialisation doesn't come without its dangers:

Concerns about oversupply in terms of tonnage from 2027 onwards are already emerging, as orders for LNG and LPG ships, as well as containers, have reached record highs over the past two years.

The Chinese, on the other hand, are pretty diversified across vessel types, with the boxships/containerships the only exposure with an elevated orderbook to fleet ratio.

Comparison to Peak Shipbuilding Capacity?

We are still 31% below peak capacity in 2010, with Clarkons forecast of 38 m CGT for 2025.

Stuart Nicoll, director at Maritime Strategies International, said that the growth of China’s shipbuilding capacity is expected to be balanced by capacity reductions in Japan and other regions.

He is expecting the global newbuilding capacity to peak in 2027 at just under 43m cgt, up from the recent low of 34.2m cgt in 2021.

That difference between forecast capacity pean and the prior peak is down to all the private yards that went bankrupt, and analysts don't see them reactivating anytime soon.

Forward Coverage

Forward coverage across shipyards is 2.9 years.

So you are now looking at 2028 to order a newbuild.

Neither South Korea nor Japan have plans to add sufficient capacity, with analysts pointing to them having issues maintaining current capacity in the long term.

Newbuilding brokers talk of how South Korean shipbuilders are positive about the short term but “really quite nervous” about the medium to long-term prospects.

Shipbuilding is no longer a high-status industry in South Korea and young people are not attracted to it, forcing yards to import overseas workers amid concerns over how they will maintain their capacity, one broker said.

South Korea, Japan and China all increasingly target "complex/advanced shipbuilding" in a quality-over-quantity approach. This is explicitly mentioned in China's 5-year plan: Quality Over Quantity: Emphasise efficiency, sustainability, and high-quality output rather than sheer volume.

Expanding Chinese Shipyard Capacity?

This brings me to the main boogie man for the shipping and shipbuilding investments.